Jason Benjamin

Jason Benjamin is a master of the mixed message. At first glance his landscapes seem to echo tourist brochures advertising ocean cruises or holiday escapes to pristine tropical beaches. Palm trees sway in the breeze, the sky is illuminated by the rosy glow of sunset. The only thing missing is the lazy holiday-maker propped up on one elbow, a cool drink in his or her hand. But it’s a significant absence: there are no people at all in these pictures.

In his metaphysical vistas of bleak, urban spaces, Jeffrey Smart would always include a figure or two. “It’s simply for scale,” he would explain, but this was never an adequate explanation. A figure in the painting allows the viewer a point of identification. We can imagine ourselves in the same position, regardless of whether that figure is reclining on a beach, standing motionless by an expressway or suspended in mid-air. Smart encouraged viewers to put themselves in the picture, Benjamin leaves us on the outside looking in.

These landscapes are seen though the eyes of an imaginary on-looker. It could be you or the painter himself, but each scene is imbued with a particular mood and feeling. In the cinema this is called the point-of-view shot, in which the camera allows us to see what a chosen character sees. This visual data is not presented objectively. Everything in the film up to that point has worked to shape our interpretation of what we see.

The prevalent mood in Benjamin’s paintings is one of melancholy, or loneliness. We look at a picture postcard view and feel an unexpected twinge of Sehnsucht – to use that untranslatable German word that stands for longing, nostalgia and desire. These are not images of pleasure but of lost pleasures remembered and regretted. It was a good time but now it’s over, and can never be recaptured. Tennyson was addressing himself to the sea when he wrote his famous lines: ‘the tender grace of a day that is dead will never come back to me.’

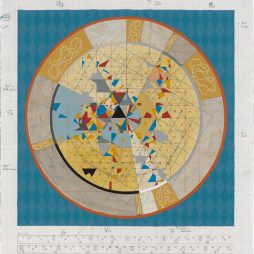

This tone, which might be described as broadly Romantic, is reinforced by the way the paintings are constructed. Benjamin is attracted to sunset, when the day is slowly expiring. He may paint a bright, blue sky but then gradually darken the canvas to produce a more muted effect. While a hyperrealist painter will invest his work with the clarity and instant impact of a photograph, Benjamin’s paintings reveal themselves slowly. His seas, for instance, are not painted with slow, broad gestures or expressionist bravura, but composed of thousands of tiny brushstrokes. He is not thinking of the operatic seascapes of Turner or Courbet, but the mechanical persistence of an artist such as Agnes Martin, whose abstract lines aspire to spiritual transcendence through sheer repetition.

In Benjamin’s landscapes those small, tight lines, as condensed as woodgrain, are set against empty skies and fluffy clouds painted with a few deft swipes of the brush. Look closely and one can see the painstaking labour that goes into every picture, but Benjamin wants us to engage with the complete image not just one aspect of its making. The labour and the loneliness do not detract from our pleasure in these paintings, they add both depth and nuance. It’s like being shipwrecked up on a desert island: it may be a tragic occurrence, but it comes with an exhilarating sense of freedom.