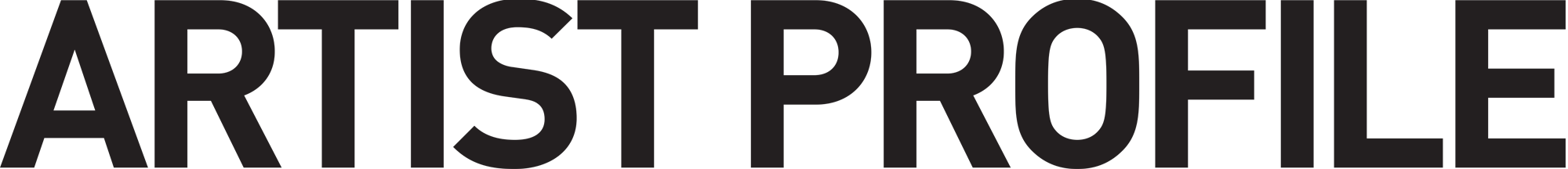

Elisabeth Cummings

Elisabeth Cummings is not a painter with a single signature. Her work is delicately wrought, possessing a palette that sways from pale to bloodied. It also moves from the intimate scale of small etchings, drawings, watercolours and gouache to imposing diptychs in oil. Sometimes she makes small ceramic 'scenes' or clay bodies for bronzes. The further she moves from her core medium the more playful she becomes but the central arguments of form, space and line are never absent.

Landscape. It is a word that seems a little bit like a solid container. A sturdy vessel for the spectacle, the scene, the entity of a view splayed before us. Still life. It sounds like something animate that has been jarred for the winter or a table where dust never falls. Yet the best examples of both disciplines serve to unravel rather than encase.

Established genres need to be broken apart in order to come alive, knitting together and ripping open or patching in and then scraping away, exposing the problem of making art, touch by touch. Elisabeth Cummings’ work was born within scenes of the interior, has traversed the landscape and clearly transcends both categories.

This year the most comprehensive display of Cummings’ career is on show. Her second major survey show Interior Landscapes, debuted at Canberra’s Drill Hall and opens at the S.H. Ervin Gallery, Sydney in May, is accompanied by a new monograph that testifies to a prolific and deftly honed body of work. Much has been made that the arrival to this pinnacle has consumed her lifespan. But perhaps too much. Cummings has always been in the terrain, making her own marks. ‘I think I needed time. It’s been a gradual process for me. I always painted, I painted as a child; it has been slow finding a voice of my own.’

The long road to her best work began with a decade of study and practice in Europe, the brief tutelage of Oscar Kokoschka in 1961, many years of teaching and the establishment of a bush studio in the early 70s, which has remained her softly lit creative nerve centre.

The last time I visited Wedderburn was on the cusp of her last major show in 2015. The walls were vibrating with new paintings and she refrained from telling me what was finished and what was still in train. The atmosphere was one of quiet revolution and a major work Monaro shadow and light (2015) was sitting on two chairs against the mottled white brick wall. This painting, with its subtle palette and dry, humid light compressed many of her signatures into one plane. Here were sheer veils of colour, dry urgent brushwork and the visual jolt, the ‘shock’ as she calls it, of a monochrome block of foliage, grafted into the frame, lifting the eye skywards.

Having the experience of seeing this work travel from studio to gallery to museum to bookplate in the space of two years demonstrates her ascension into canon but there is nothing like the first encounter with her paintings. With something like the tactility of a textile or a weathered beloved talisman, they have a strong sense of inhabited space that is both welcoming and immersive. They let you in.

Cummings’ work is diverse. It is impossible to anchor down into a singular motif. Yet over the sprawl of so many vivid oils there are certain links. Like Vuillard, there is sometimes the presence of a single dark form in the composition: a figure, a tall bottle, a stand of trees that lends gravity. And sometimes within the belly of her larger paintings, Cummings will trail a line that curves like an unfurling rope or the bend of a road traversing the swell of a hill. Her trajectory from a tonal painter typical of her own generation to an extraordinary colourist with a singular painterly language seems to arc like this line. Gradually climbing until the vista comes blindingly into view.

This is not an artist who is easily pleased with her own work. In conversation she concedes to a patient/impatient creative nature yet her measure of the success or failure of a painting outweighs any sweeping sense of achievement: ‘A retrospective can be a shock. The best element of the Drill Hall show was that it was beautifully hung and so well lit. It is strange to see them. It’s like a diary of that part of your life. There are always doubts about certain paintings but when you say “this is done you can go” whatever it is that makes you stop, then you let it go. Yes. Yet there are a few paintings that remain unfinished.’

When a large work surfaced in auction recently Cummings immediately reclaimed it with a tentative plan to paint it out and refresh the entire thing. Completion in her terms meets a deeply personal standard. ‘I am dogged,’ she concedes, ‘perhaps tenacious.’

No one could be more aware of the layering, accretion of time and discipline needed to generate paintings with such a sustained surface, resolute colour and compositional tension as the painter herself. But the touching contradiction of Cummings in conversation is how few words she has for such a sophisticated process: ‘With some paintings I feel good about them. Some. Some. Not all. Of course you are always wanting more. One’s greedy. You want to go further. You want the next painting to be’ (she pauses for a long thoughtful silence) ‘you want the painting to be alive. I want it to move. Not always achieved but that is what I want to attain … I want them to have that pulse of the paintings which I love, that movement, that’s what I want for my own painting but it is elusive. It can’t be planned for. And I guess that why one keeps on painting.’

The experience of a firmament is clear in works such as the diptych Edge of Simpson Desert (2011) and Golden Day (2015). Her most potent interiors such as The Green Mango B and B (2006) or Red Room at the Green Mango (2006) attain the pulsing simultaneous colour of the Post-Impressionists. But their surfaces vibrate in a way that is febrile rather than decorative. Moving between interior, landscape and abstraction also transports her work between the scale of intimate and epic spaces.

Many writers have noted that it is Cummings who best understands the strange, dispersed, untidy quality of Australian wilderness. Luke Sciberras, her friend and frequent plein air partner sees her process as one of actively restructuring it all. ‘Dissembling the landscape and retelling it with its essential tone. And colour and a pace all her own,’ he says. This pace keeps time with unpredictable materials. Bush light can be both broken and mutable. It is something she has studied by countless trips into disparate landscapes as remote as the Pilbara, Mungo, the Flinders Ranges and Warburton.

Her most recent journey inspired a series of prints: ‘I did some works recently on large plates, I got a nice reasonably fat twig and a smaller twig and we did a sugar lift. You can either use a brush or a line, but with this twig I just drew, I had a great time. I’d been in the national park in south-west NSW with Euan Macleod and Michael Kempson. We had been there for three days and so I did a bit of work on Mungo, it was a very free interpretation, that was just the black and white.’

Cummings expanded into printmaking in 2001, initially as a teaching exercise with master printer Michael Kempson. Unlike many painters, this one enjoys the communal spirit of both travelling and learning with other artists. And in printmaking many hands are needed.

At first the process provided stark contrast to her rapid-fire painting methods: ‘I find it difficult to judge my etchings because I think like a painter. The limitations of etchings are technical. My way of composition is usually to throw down a lot of stuff (forms, lines and colour) and then start eliminating. My way is to be changing things all the time. But in etching to do that is enormously time-consuming, almost arduous. Yet there are rewards. I love the quality of the dark line, it’s a whole other line, so different from drawing where you can dart in and out with colour.’

Because so few of her works are solely linear, Cummings brings a wildness to printmaking and she says very few of her printed works on paper are heavily planned. Her earliest etchings such as ‘Dogs Under the Table’ and ‘Piano Room’ (both from 2001) are some of her favourites, perhaps because she knew so very few of the limits or technical straits of the craft.

Her compositions are pushed into simpler forms in this medium. Pilbara Landscape (2005) may have featured several more colours if executed in paint. Here is a metier given to a different sort of sensuality where lines sink into paper instead of paint and the artist’s gestures can also seem more explicit. Love for the land always seems evident in her work but in the small coloured etchings there seems even more tenderness, a certain vulnerability of touch. Flinders Journey (2007) melts mountains into molehills, softening the scene the way a child recasts hard landforms.

The grand standing presence of a vast diptych might not pinion Cummings’ next gallery show. By necessity and perhaps alternation (with her major survey) there will be smaller paintings, gouaches, cast bronze figures and print works. You don’t need to study these outer constellations to understand her universe.

Without doubt painting is her toughest reckoning. This is the place where she admittedly seeks the deepest gravitas and works hardest on structure (both its creation and implosion). This is also the locus of her colour, finding new contexts and her line pressing on for a startling turn. Experimentation and the will to shock deep-seated aesthetic reflexes into a new medium or an ungoverned pathway seem natural to Cummings. ‘When my arm was healing (last year) I started to draw with my left hand and that was good because you develop a certain facility with your right hand and it’s great to be able to break through that if you can. You can be aware of your own habits and skill. It’s hard to challenge though that’s where Picasso was such a master but very few are given the capacity to do it. One wants to surprise oneself with a different gesture, with that hand, arm, line, shape and colour.’

A few days after our meeting and many many months after a break from Wedderburn, the painter is returning to her studio. The cycle of her making follows the daylight. Some canvases begin bare, others are being revisited. Here she cleaves away from the retrospective, shattering habits, speaking to colour, looking through new branches.

This article was first published in Artist Profile, Issue 39, 2017

EXHIBITION

Elisabeth Cummings | Eastern Arrernte country & Morocco

7 July – 1 August 2020

King Street Gallery on William, Sydney