Sara Maher and the expression of light

Following a chance encounter with mysterious film negatives on her studio floor, Sarah Maher’s home studio has become an active participant in the development of her work, acting as both inspiration and production tool. For the artist, the negatives “called to be listened to and followed as an offering of unknown generative potential.”

Sara Maher was the first artist I met in Tasmania. I encountered Maher gently arranging tiny drawings and prints in a tree for the 2004 Mountain Festival Sculpture Trail. It was a generous work, and despite its public location, deeply personal. The illustrations stemmed from an intuitive “drawing and writing process” that Maher and her sister continue to this day. To the artist, the work embodied “a magical connection . . . a sisterly connection.”

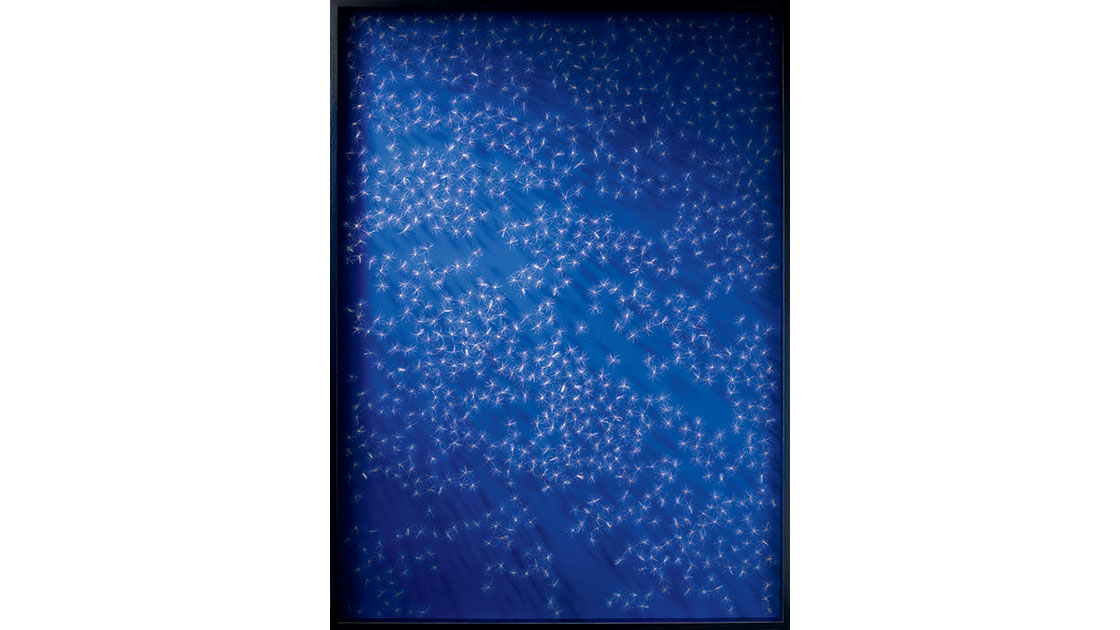

Maher takes inspiration from the local natural environment and cultural history, but her work is far from representational. Maher embraces chance, intuition, and natural processes in the making of her prints, paintings, and drawings. The ghost-like image in Thinking in my Ancestor’s Shadow, 2021, for instance, formed naturally in response to the surface qualities of the underlying birch panel, the artist noting “the material will reveal things you can’t plan for.”

Maher grew up in Sydney and considers her initial training at the National Art School significant. “My work now is a result of having lived in two locations,” she says. It was during this period that she learned “you can think about paint, and you can think through paint.” Maher moved to Tasmania in 2000 and continued her studies at the University of Tasmania School of Art in Hobart, prompting a distinct “change of direction” in her work.

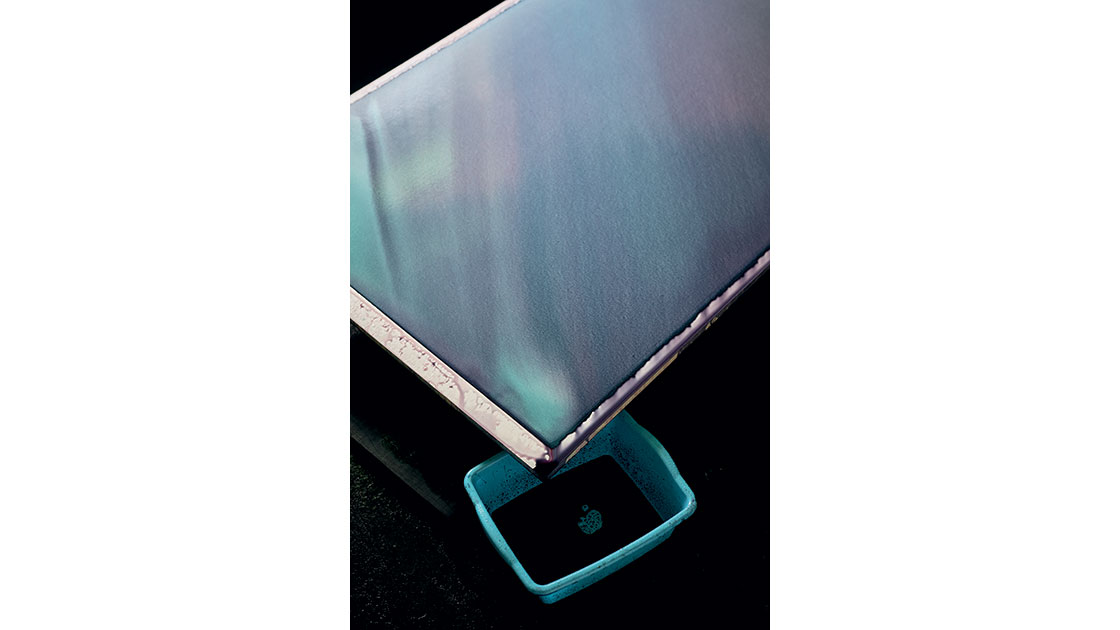

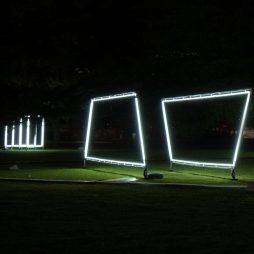

Cultural and wilderness residencies in places like Lake St Clair, Cradle Mountain, and Queenstown have played an important role in the continuing development of the artist’s practice, providing the time and space to make work in dialogue with the landscape, and allowing the artist to “navigate a sense of place, [or rather] a sense of self in place.” A 2020 residency on Bruny Island explored this personal relationship to place within the context of troubled histories, resulting in the striking Open Listening (Lunawanna-alonnah/Bruny Island), 2021, which won the Tidal.22 art prize. Maher describes the artwork as “analogous to my treading lightly as a settler of Irish-European descent, within spiritual and storied Aboriginal lands.”

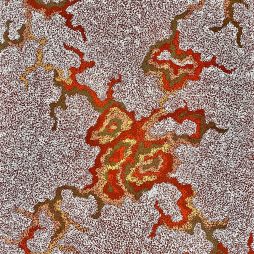

An earlier cultural residency on Maria Island—a former penitentiary, now bucolic national park and historic site—prompted her to “start thinking about the boundary,” both physical and psychological. She took impressions of the walls of the island’s remaining buildings, as seen in Limbus, 2006. A similar process was used in Breathing Holes, 2008, created inside a convict-built solitary confinement cell on the Tasman Peninsula. Working in oppressive darkness, the process of rubbing produced a pattern of erasure, described by the artist as akin to “a faint constellation of stars.”

While residencies are central to her practice, Maher stresses, “I always return to my studio. The studio space becomes a repository, a means of recall and processing and reflecting. [I want to be] responsible in my practice but keep an aliveness in my art.”

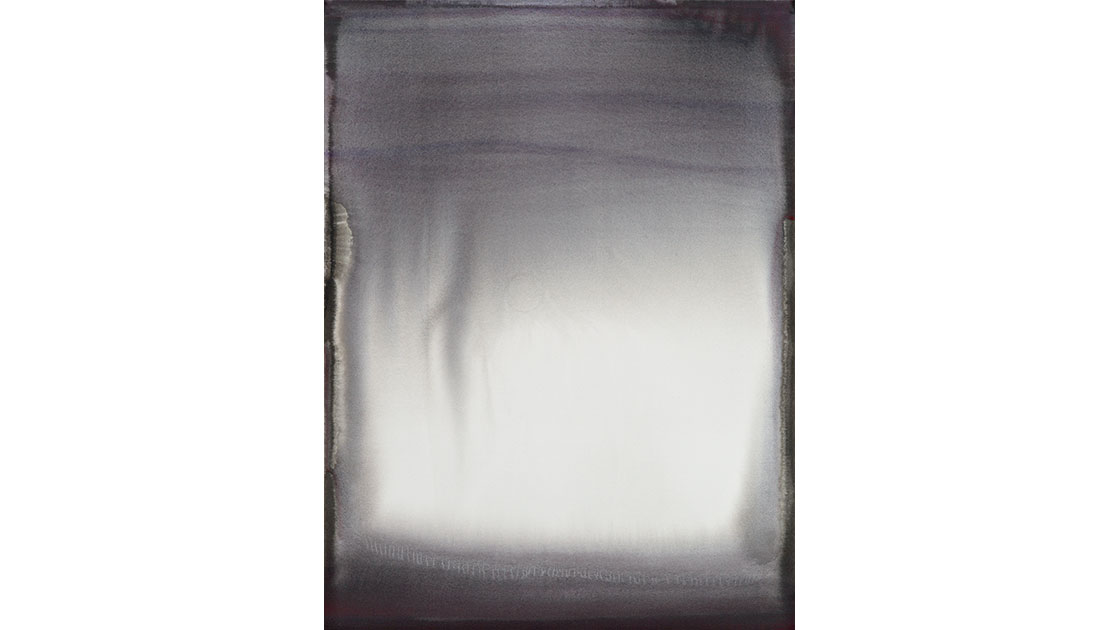

For her upcoming solo exhibition, Gravity Portal, at Contemporary Art Tasmania (CAT), Maher is producing a series of “colourfields,” as the artist describes them. The project was prompted by the discovery of a 1930s film negative of two sisters that slid out from behind a fireplace (or “gravity portal”), in the “wet room” of her home studio. “The encounter with the negatives didn’t feel spooky,” Maher assures me; “it felt like the house was offering something at the time that [CAT curator] Kylie Johnson and I were coming together. I sensed a parallel world, implicit and consciously unwitnessed, but nonetheless pressing against my experience.” The wet room is the first encountered on entering the house and the contrast between the domestic architecture and the room’s blackened sprayed walls is shocking, with layers of indelible ink seeping deep into the cracks of the walls.

Maher unpegs blankets from the windows, allowing me to better see the soft colours in the colourfields that dot the living room. In the adjoining sunroom, other colourfields are being deliberately sunned or faded. She points to The Sky is my Gravity 1, 2024, noting that it was sunned over summer, which gives it a different quality to a winter sunning. The roses that bob along the outside of the sunroom are significant too, acting as both inspiration and part of the sunning process. When she moved into the house almost twenty years ago, she’d neglected the roses, but on finding the negative with the two sisters posing outside the house, she threw herself into gardening. Maher observes, “I imagine what they might have felt for this place I am feeling. Here, the past and present reverberate.” The Rose Inhabits my Mind, 2024, is “about the colour of the roses, and the scent, and the sisters who may have planted them.”

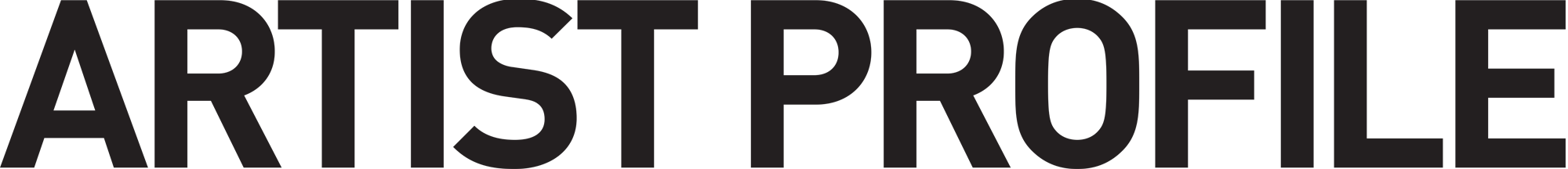

Prior to sunning, the colourfield panels are produced over various sessions, with the front of the paper stuck to a board. Inks are poured over the tilted work, the liquid captured, and repeatedly repoured. Maher explains, “I have a sense of where the ink is bleeding, but I’m not completely aware. You couldn’t complete this if you were fully aware.” The resulting colours are soft and delicate, with no one panel the same. As Maher says, “they look like expressions of light.”

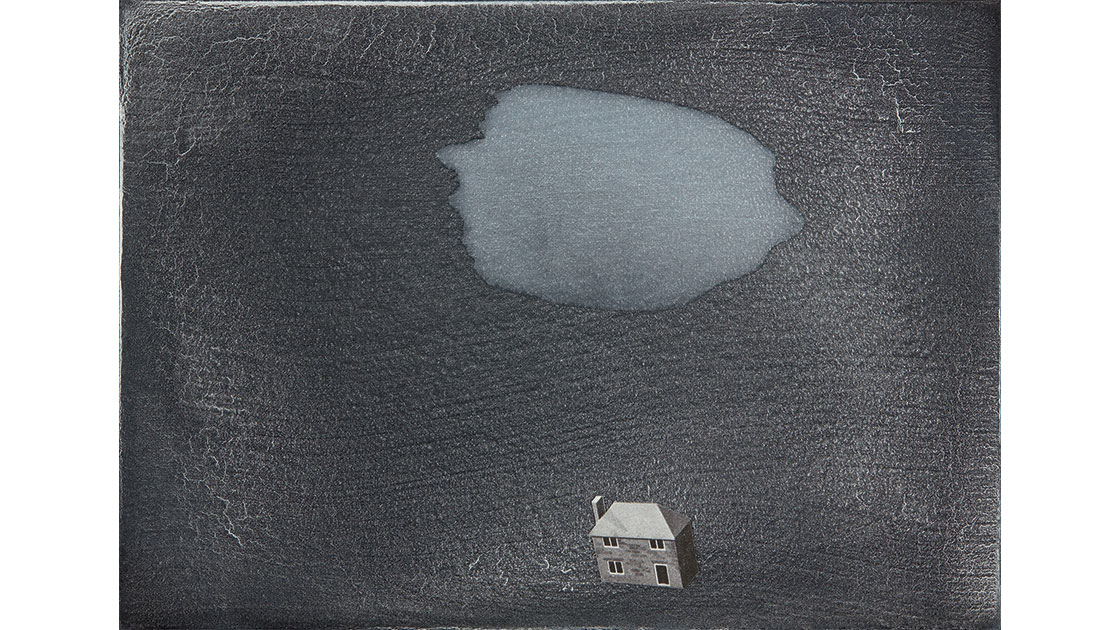

Maher describes her colourfields as “more airy and elevated” than her last body of work, even though “they’ve come out of a trajectory,” referring to the miniatures in her 2023 commercial exhibition at Bett Gallery, Hobart, which embraced the “fragmentary world of story and narrative.” Maher likes to shift between big and small, and the scale is always significant. “Small works have humour,” she notes, while “the large are super serious.” Her miniatures use intuition and materiality to guide her mark-making, resulting in uncanny images that hint at the figurative, while maintaining the artist’s desired “dream-like quality.” The postcard-sized, Ground Control to Grandma Smith, 2023, was titled after Maher’s mother remarked that the pink shape was “the spitting image” of the artist’s great-great-grandmother.

Grandma Smith takes on a new life in Maher’s current body of work. Inspired by stories of her ancestor’s fine needlecraft skills, some of the colourfields have ghostly shadows of heirloom needlework, produced by draping ancestral objects like tablecloths and shawls over the sunning colourfields for months. Maher views Grandma Smith’s enduring crafted objects as “psychically charged . . . like a communication across worlds.” The artist believes that “stories are encoded in these objects,” and by using the handcrafted objects to produce new work, she’s “holding the [craft] knowledge in another form.”

While the deliberate use of non-lightfast ink is taboo in commercial art practice, the non-commercial nature of the CAT show has freed Maher from such restrictions, allowing her to experiment with light-sensitive Japanese inks of “vibrant colour resonance” that she describes as “alive with energy.” She admits, “it’s nerve-racking making work that’s fading. It’s recalibrating my thoughts on what is aesthetic. It’s all about loss.”

However, it’s clear the notion of the “artwork disappearing over time” excites Maher. “It’s nice to recognise that an artwork isn’t just a vehicle for communication,” she explains. “It reveals its own personality and being . . . it’s like a living experience. It has its own agency.”