Holly Greenwood

Holly Greenwood observes the social and cultural dynamics of the pub with depth, detail, and an abiding affection. A new series of oil on board paintings showing at James Makin Gallery, Melbourne, pictures the negative space between people in these quintessential venues, as Greenwood considers our attempts to connect with community in the wake of the pandemic.

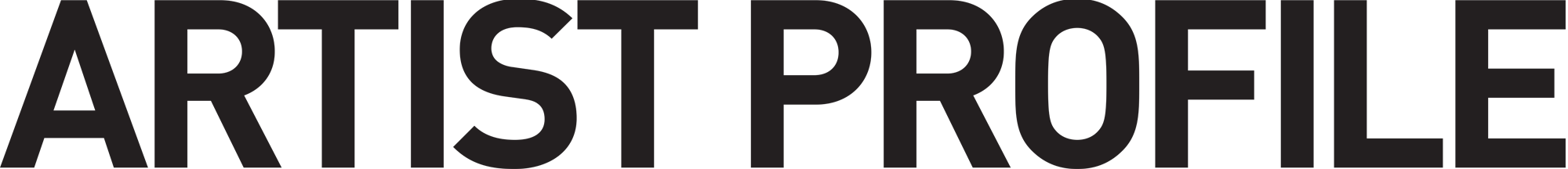

The central figure in Cats on toast, 2022, has their back to us, the checks on a flannel shirt giving perhaps the most telling clue to their character. A swoop of black oil paint in the centre of their head could be a bald patch; equally, it could be a section of dark hair; more figuratively, it could gesture to the internal, affective space within the figure. To the right of the frame, a secondary figure’s face is obscured by this same encroaching darkness. Deeper into the picture, a third figure’s forehead and nose, seen in profile, dissipate out into this darkness like smoke (perhaps from the cigarette held by the red fingertips of End of the Night, 2022). People populate this scene in earnest whispers, cautious and half-heard across the pub. They’re there to share something of themselves, or to make an attempt at this sharing through the strangeness of both the social life they find at the pub and the emotional life that they bring to it.

The works in Greenwood’s I Was Born Here, I’ll Die Here, are expanded and trans-mediated versions of gouache studies frequently taken in situ at the pub. Australian pub culture has been a long-held interest for Greenwood, which she has explored in previous solo shows including Paintings from the Front Bar at James Makin Gallery, and Last Drinks at Olsen Gallery, Sydney. Perhaps the best-known other thread in Greenwood’s practice is her landscape painting – exhibited notably at Broken Hill City Gallery earlier this year in Petrichor, a group show with Ondine Seabrook and Bronte Leighton-Dore. Uniting these two faces of Greenwood’s practice is both the artist’s close and emotional relationship with the object of her observation, and a sensitive understanding of our relationships to place in Australia, as ambivalent as they often are.

Just as Greenwood’s landscapes push back against some of the conventions of their genre, so to do her observations of social life in the pub. Where artists in the European tradition painted scenes of urban life through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by looking outwards on the the street – to observe people strolling in the park, driving down the street, or sat outside reading or drinking a coffee – Greenwood’s gaze is turned inwards, both spatially and conceptually. In a way, we might think of Greenwood as a kind of anti-flaneur: rather than walking through the city, as if wanting to be seen in her act of seeing, her paintings seem to emerge from periods spent installed in some corner, watching and listening to people slowly open themselves up as if she wasn’t there to take record of them.

Many of these scenes register moments of surprising tenderness, ambiguity, and strangeness in public. Gestures say a lot here: there is the soft slouch of shoulders above a glass of bourbon, the self-assured, delightful, and delighted raised pinky finger around a glass of red wine, and the recurring pairs of torsos positioned parallel to each other at the bar, in conversation or in shared silence. The titles of many works also give subtle clues about the moments observed. There’s The Climate Sceptic, 2022, whose hands we see wrapped around a drink, as if hesitant to speak their mind. Then there’s The Wake, 2022, in which two women are seen discussing which vegetables were in season in their gardens, having just catered for the titular wake. Incongruity, hesitation, and vulnerability are woven into the carpet at Greenwood’s pubs, flashing out in eloquent moments from the darkness.