David Hayes

David Hayes paints high-gloss iconic works which are reminiscent of pop art – but instead of celebrating mass culture, employ powerful symbolic imagery to dig deep into the human condition. The works are both personal and gender-reflective, and explore our mortality, survival, and desire to live with hope.

David Hayes will tell you himself that he is just a middle-aged white guy painting the human condition. That’s certainly not a throwaway line. He does deeply examine his own maleness and its entrapment in modern-day and historical conflict. The notion that we are always learning is an important principle to him. When I mention the word “self-taught” when asking him about his professional art career, he says everyone’s self-taught. This is despite having a university medical qualification in anatomy and employing this knowledge skilfully when painting a portrait. He literally paints the bone structure first, then the muscle and skin in a meticulous, layered process. He grew up in Brisbane and drew and painted from a very early age, but cartoons, comics, and Disney provided his only visual input. In turn, through his own meticulous experimentation over time with materials and technique, he has transformed this pop genre into powerful statements about the human condition. Again, he says, you must understand where you have come from.

In Hayes’s early striving for that pop-mechanical look to his paintings, he experimented with finish. He had no time or space to work with oils so he focused on how he could alter the acrylic paint surface. Initially he started with egg tempera to gain a smooth matte finish, then moved on to resin after learning how resin is applied to surfboards, and finally found a car detailer in Bowral, New South Wales, who could give his work the lustrous finish of oil paint. From the early works through to the present, Hayes places a central, highly detailed figurative image in front of a consistently toned one-colour background. Without the high gloss finish the work would appear almost like a graphic illustration, but with it, the central image is captured in time like an insect in resin.

The early soldier paintings capture the full plastic three-dimensionality of toy soldiers which are now larger than life, in action, and brightly coloured in either red, pink, orange, or green. They are strangely iconic and representative of a world where war is taken for granted, its horrors unseen, and action playful. These paintings are the beginning of Hayes’s exploration of masculinity via robust, traditional military analogies. In some of these works he adds a life-sized bullet casing that is a sign of “real” war, or a butterfly as a sign of life.

As his works progress, he begins to hone his metaphors and his compositions. The bullet provides the metaphor but also anchors the composition. The bullet casing becomes a vase filled with flowers. Hayes states that “I realise that I need, like, and identify with having a cold, solid element paired with something delicate and fragile.” These works sit somewhere between the symbolic and metaphoric, symbolic of a reboot of life after war and metaphoric in the bittersweet coexistence of life and death. A later work, One Good Man, 2019, appears to represent the further domestication of masculinity as the bullet shell is almost replaced by toile décor, and bright red flower petals reach out of the vase, but according to Hayes the work represents something more macabre. He retells the story of the homegrown terrorist act where an English soldier was decapitated, and how the world can change in an instant. For Hayes, such incidents draw him to look deeper into the human psyche beneath the shiny veneer of daily life.

In another body of work the flowers, viewed from above, become an iconic burst of life not emerging from the bullet shell glimpsed in the centre, but rather aiding and abetting the bullet in hitting its target. Full Petal Jacket, 2017, emphasises the penetration of life into the body whilst Rainbow Warrior, 2018, marks the release and winning of LGBT+ rights after the yes vote. And yet, Infinity, 2019, serves to remind us that the flower hand grenade brings an expansion of life but also a reminder that death is always hidden. These works presage a new compositional direction whereby the imagery becomes more emblematic, and the metaphor of the bullet begins to disappear. In Lionheart, 2021, the bullet is replaced by a bronze lion. Whilst this work is a commissioned portrait of a couple, it continues Hayes’s interest in the light and the dark, the hard and the soft. Here, the dominant partner is cloaked in the softness of the other partner. Also creeping in are subtle references to primitive masks.

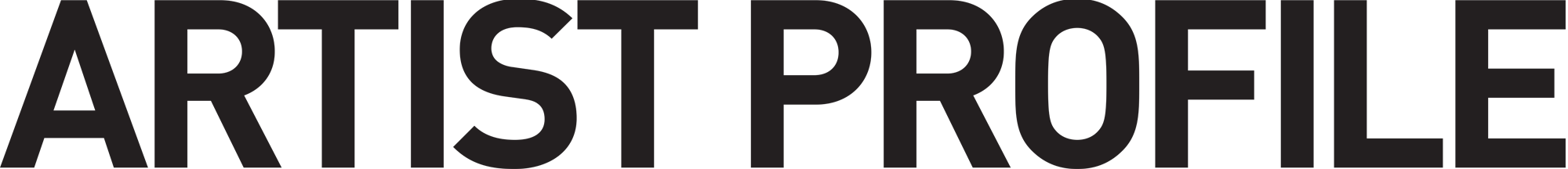

At the same time as Hayes’s marriage broke down, the world also changed forever. As he says, “Everything was so perfect and then nature and the universe colluded to change the world forever with Covid.” Hayes’s attention turned to our follies and our own fragility. What we see now in the work is a scrambling together of a mix of ancient, tribal, colonial, and contemporary imagery such as emblems, coats of arms, and busts that reference man’s vain attempt to achieve immortality. Several of the works are directly about the devastation of his own personal loss. In Red Baron, 2022, he is the dead magnolia pod, a skeletal figure with a wobbly crown that references past glories, and in Phoenix, 2021, he is back in the hunt – coming back up and evolving again.

In his new exhibition Brave New World, the bullets are gone, replaced by ancient busts. These works represent our tour of duty through two years of the frozen winter of Covid. Out of the solid ceramic and stone busts that represent our desire for immortality and grandeur bursts the bird of paradise flower that not only represents a Napoleonic hat, but also the Covid spike protein. In Lord Delta, 2022, the reductive colour palette and its reference to the dominant use of red, white, and blue on national flags suggests the global impact of Covid. Taking this further, The Alpha Campaign, 2022, compares the spread of Covid and our battle with it to a military mission. By combining the image of a Western blot test, a method to analyse protein structure, and a lapel badge that represents a military mission, Hayes is not only alluding to the artistic exploration of colour but also the search for new life through art and science.

As he says, “As worlds move on, as they have done before, they eventually may crumble, and life sits dormant in the ashes. The human spirit is robust however, and rebirth occurs.” Hayes is documenting his own and our collective journey through that process.