Stop Making Sense

For Bundanon Art Museum’s first exhibition of the year, curator Sophie O’Brien has selected artists whose practice involves different approaches to collaboration and engagement with community. The selected artists demonstrate, in varying degrees, a unique awareness and appreciation of their surrounding environments.

I approached the exhibition Thinking Together: Exchanges with the Natural World with caution, thinking it might be a problematic and questionable foray into collaborative exchange. It’s a popular phrase that gets bandied about in the art world. Overall, I was pleasantly wonderstruck and left believing that the works selected by Sophie O’Brien were more akin to time-based pieces with or without traditional performers. I have in mind the three commissioned works of Robert Andrew, Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan, and Keg de Souza, which unfold over a period of time during the exhibition. Despite the quality of the other works, I am not convinced they were actually necessary.

The main gallery is initially dominated by Filipino artists Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan’s REFECTIONS/HABITATIONS, 2025. The work is already well established like some giant siphonophore, its gridded timber frame acting as a skeletal structure. It supports numerous colonies of smaller variable cardboard structures providing a habitat for more to be added throughout the exhibition. The work is meant to resemble a fallen tree and serves as a nod to Arthur Boyd’s drawings of trees and the landscape surrounding the gallery. The artists remind us that even a dead tree can continue to provide a home if not a canopy. It’s no longer one thing but an ongoing infrastructure for many other living things. The Aquilizans invited audience members to contribute to the sculpture by creating their own mini constructions with materials located in an adjoining room.

Keg de Souza’s Growth in the shadows, 2025, uses fungi and mycelium from the Shoalhaven landscape to illustrate the interconnected networks of species. Live audio biofeedback allows the audience to appreciate just how social these specimens are, even when sealed in 1830s Wardian cases. The cases act like the terrariums of today by providing a protective environment; they were used to transport delicate plants from overseas in the nineteenth century during sea voyages. The cases are named after the English doctor Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791–1868), despite a Scottish amateur botanist named A. A. Maconochie (1806–1885) creating something similar almost ten years earlier. De Souza uses the glass windows on these cases to display interdependent networks between fungi and plant life, and possible similarities to historical scientific designs and mapping that illuminated earlier ideas about human thought.

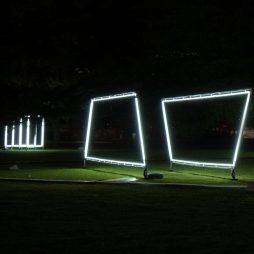

Yawuru descendant Robert Andrew is a thoughtful artist. This was evident from his talk on site when he did not rush to answer a question from an audience member. Some questions need time before replying, or even left unanswered. This reasoning is carried into his process-driven work. In new eyes – old Country, 2025, the use of technology in this kinetic artwork can be misleading or even some sort of misdirection, with its mechanical armature moving the charcoal along the wall. It’s a slow “meditation” where the mark making is barely there during the first days of the exhibition. There’s more charcoal on the floor than on the wall at first viewing. But it promises over time to mix past and present with what was seen before and how it’s remembered or more precisely translated now. A video screen is attached vertically to the mechanism as it traverses the wall. It shows the footage captured at various sites along the Shoalhaven River by a drone. The artist is looking back at the past but speculating in the present. The work is not trying to be absolute or even anthropological in its presentation but rather it’s transcribing the unwritable. Each layer contaminates the original, informing or obliterating it; which action is which, or more valuable is not clear, and does it matter?

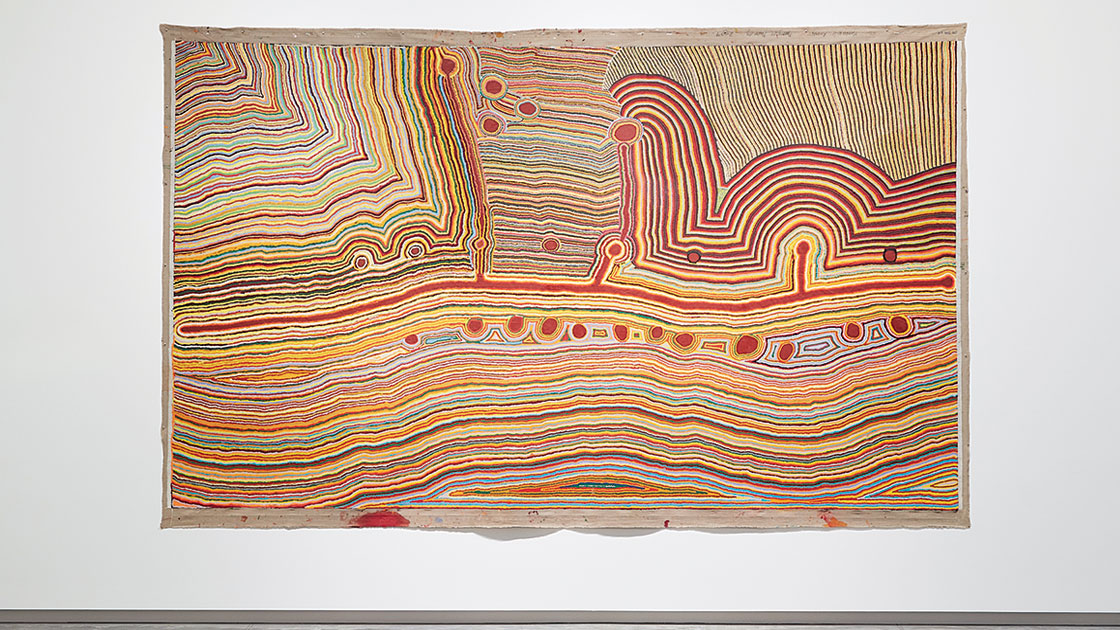

Other static works in the exhibition explored interactions, connections and the passing of time. Martu artists from central Western Australia have two large-scale collaborative paintings, one in each gallery. Martumili Ngurra (This is all Martu’s Home), 2009, by six female artists from the community of Parnngurr, identifies important cultural sites like waterholes, including those on the Canning Stock Route. The work is briefly summarised by one of the artists, Ngalangka Nola Taylor: “painting the ngurra, they do it to remember their connections.”

In the second gallery is Kalyu, 2014, painted by nine artists also from Parnngurr, and made as a response against uranium mining exploration at the edge of Karlamilyi National Park. Not surprisingly, this area is exempt from the 2002 Martu native title determination. The painting resists this by signifying the interdependency between the areas in the regions, not least because of the desert’s hidden waterways.

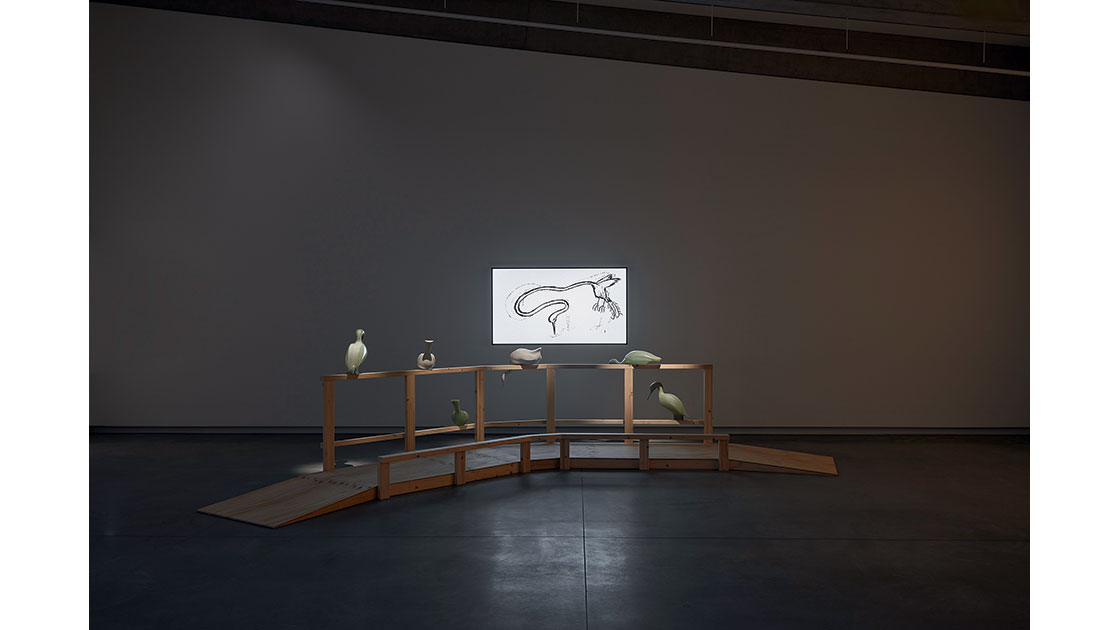

Thai-born, New Zealand-based Sorawit Songsataya’s work, Comfort Zone, 2021, focuses on the kōtuku (eastern great egret) that is found throughout Asia, the South Pacific, and Australia but is rare in New Zealand, where it only breeds near Whataroa. Songsataya uses sculptural objects to incorporate and frame a screening consisting of footage of the kōtuku in their nesting grounds. Along with animations, various imagery and an almost random voiceover there is a sense of incomprehensibleness. However, the kōtuku wherever its location is generally considered to be a good omen.

My initial reaction to watching Tina Stefanou’s Horse Power, 2019, made me think I was seeing a forgotten land where horses were revered and decorated in medieval outerwear. The use of black-and-white film creates the effect of lost archival footage, evoking an older, traditional time. Reclaimed fishing nets adorn the horses, with stitched-on keys and bells resounding their presence with each flick of the head. The impression is of a treasured animal from a nomadic tribe. Later however, as I listened to Stefanou speaking during her artist talk, she informed the audience that we were all bourgeois because we were visiting the gallery. This was a naïve statement, as she had no way of knowing about the audiences’ background or personal history.

She also repeatedly referenced her own “peasant” ancestry, and the repetition of this statement made me wonder whether this was some sort of strategy to authenticate her work. It certainly altered the way I experienced the artwork and changed how I’ll think about her other works in future. I cannot stop thinking about the rescued and retired horses in the video. I wonder whether they might have preferred being left in peace instead of appropriated into Stefanou’s video work or not ridden “gently” during their dying days.

Comprehension can depend on perspective. Understanding can be contingent on context. There are always multiple views even if you are recalling the same thing that someone else has experienced at the same time. I keep thinking about Andrew’s work and how meaning can be lost in translation—can it be lost if it’s beyond comprehension? Can it even be understood without knowing the culture? You might have to think about meaning differently and maybe just let it develop, as understanding requires time, and maybe hindsight. Seeing the work fully may even require you changing your mind.