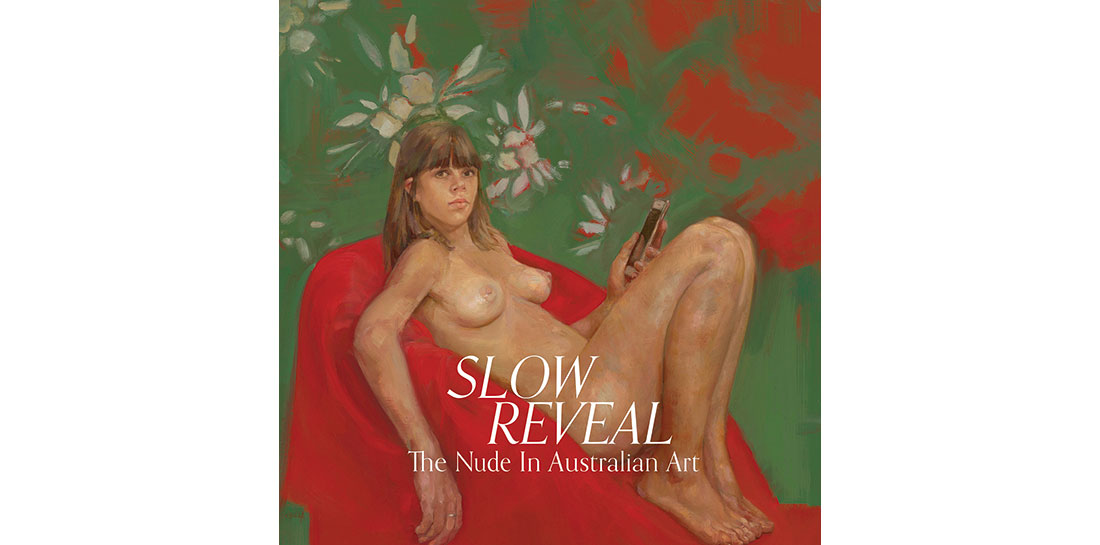

Slow Reveal: The Nude in Australian Art

Paul McGillick has produced a valuable survey of a subject that has not been properly studied before. The book contains a remarkable range of drawings, paintings, and sculpture from colonial Tasmania to the present day and raises important questions about historical and contemporary uses of the human figure in art.

Paul McGillick has brought together much fascinating, and often relatively unfamiliar material in what is effectively the first study of the nude in Australian art. That nothing of the sort has been attempted before is not as surprising as it may seem, for the erotic vein is not prominent in the history of Australian art—with notable exceptions like Norman Lindsay and Brett Whiteley—and the more serious use of the nude in grand narrative or allegorical paintings was confined to a few muralists like Napier Waller. Meanwhile academic commentators and institutional curators in our own neo-moralistic age regard representations of the naked body as an ideological minefield.

Free of such anxieties, McGillick reveals that images of the naked or the nude—to recall Kenneth Clark’s famous distinction—are both more common than we may think in Australian art and present from almost the earliest days. Many were no doubt surprised by the revelation, a few years ago, of the erotic nudes painted by T.G. Wainwright; but Thomas Bock’s frank and intimate studies of his mistress, also from 1840s Tasmania, are perhaps even more remarkable.

These were clearly private works, however, and neither the nude nor the figure in general plays a leading role in Australian nineteenth century art. One of the main reasons for this is that the most significant genre at the time was landscape—from Glover to Martens, von Guerard, and Buvelot—and landscape painters were not usually taught figure drawing. Apart from William Strutt, Tom Roberts was the first to be properly trained in this way, and that is why his oeuvre includes important figure compositions such as Shearing the rams, 1890.

When academic art teaching began in Melbourne and Sydney in the 1870s, it brought with it the life class and figure drawing as the central pillar of professional art training, even though access to naked models, as the author points out, remained controversial in the ambience of Victorian prudery. From this time onwards, all serious artists produced at least some figure studies while at art school—like the fine study by Streeton on page twenty-four—even if they did not use the figure in their later professional work.

There is a very clear difference between most of the painted nudes in this book and most of the sculpted ones: the latter, in the hands of Bertram Mackennal or Rayner Hoff and his (mainly female) pupils, as well as some later artists, evidently possess a monumental authority which most of the drawings and paintings lack. This fact could be better accounted for, and it raises a question with the way the subject is framed from the outset.

It is often assumed that the nude is a genre; but if that is true, it is only in sculpture, whose natural subject is the human figure and which, from its beginnings in our tradition in the carved figures of ancient Greece, conceived of the human body as ideally beautiful, and of that beauty as a metaphor of spiritual harmony and dignity. Only in sculpture can the figure be a self-contained subject.

In painting, the figure belongs primarily to the genres of narrative or allegory. The pre-eminence of so-called history painting in academic theory explains the centrality of figure drawing in the academic curriculum. But narrative painting presupposes culturally shared stories—whether scriptural, mythological, or historical; and with the breakdown of shared narratives in the modern world, narrative painting, and hence figure painting, faced a crisis.

In earlier times, famous nudes that McGillick cites, like Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, 1510; Titian’s Venus of Urbino, 1538; or Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, 1647, were exceptions, still nominally attached to the history genre by their mythological labels. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, increasingly independent “nudes” reflect a crisis in the tradition, and those painted by Degas or Cézanne are manifestly figures at a loose end, actors without a play to perform in.

The great majority of the nudes in this book, especially from the last century, are essentially figures that have half escaped from the life class but not really found their way to any higher narrative purpose. While there was a clear distinction between model studies and painted figures in the early modern period, the modernist nudes remain mostly pictures of models. Sometimes they become portraits and thus find a home in another genre (life studies are not portraits). In some of the most interesting cases, they become self-portraits; in others, as in the pastels of Janet Cumbrae Stewart, they are images of barely sublimated desire.

The modern nude is thus an inherently problematic category, but also one which, in its very ambiguity of purpose and context, raises urgent questions for artists today. McGillick has provided, in this thoroughly informed and often insightful survey, the material with which we can effectively consider some of these important questions.

Book

Slow Reveal: The Nude in Australian Art

By Dr. Paul McGillick

Yarra & Hunter Arts Press, 2024

ISBN: 9780975643211

RRP: $79.99