A sense of place in the art of Tina Stefanou

Tina Stefanou works with experimental forms of performance and visual art, creating experiences that prioritise embodied relationships and multispecies encounters in community and place.

Based in the peri-urban region of Wattle Glen, in Victoria, her practice is informed by the Greek heritage of her immigrant family and their working-class experiences. There is an unmissable diasporic perspective and class sensitivity that transpires through her projects. Although the focus of her work is directed towards the possibilities of fellowship, the building of cultural commons, as well as environmental issues of sustainability, there is also an underlying acerbic attention to the way class boundaries, racial hierarchies, and cultural capital are mobilised.

Stefanou’s projects range from large-scale installations to modest gestures in specific places. She has used video and conducted vocal workshops. Stefanou is accomplished in performance making and committed to using art as a tool for social justice. This breadth of experimentation with media and the deployment of a range of styles by Stefanou is not to be confused with an undisciplined or naïve approach. On the contrary, it is consistent with the well-established contemporary genre of socially engaged art. Stefanou spends considerable time working with and hanging out in different communities and areas. Her practice is informed by the ethnographic approach but her artistic imagination takes the insights into new dimensions. Her use of music and film, performance and sculpture stimulate wider sensorial experiences than the conventions of ethnography permit.

Stefanou’s attention to performative actions and deep engagement with community groups culminated in the production of a major work The Longest Hum, 2021-ongoing. Its first iteration was in the regional town of Kandos in New South Wales, and despite the travails of lockdown, Stefanou arranged to sing with diverse groups of people in settings that ranged from concert halls to working-class pubs. Over two hundred people and their animal companions gathered to form a constant hum. The hum was broadcast on community radio for its duration of ten minutes. Her use of voice and breath is cosmic, and Stefanou aims to extend this project over twenty-one years to create what she calls a “collective planetary vibration.”

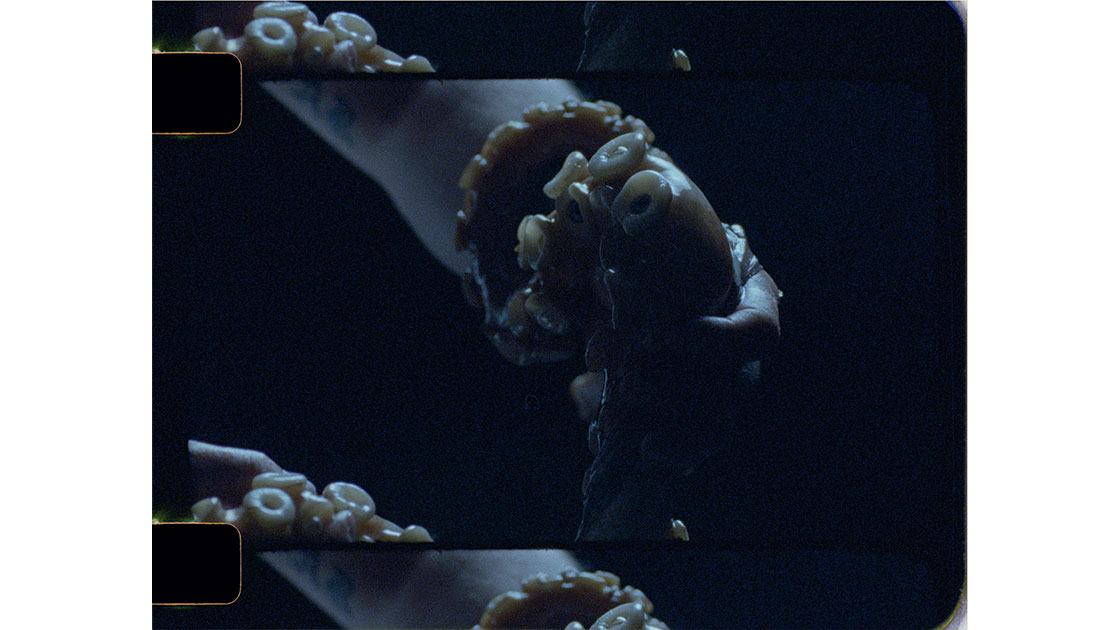

One of the fascinating themes in Stefanou’s practice is the transmission of energy. She finds it in ordinary places, and among people who have been displaced. Stefanou is alert to the way people connect the knowledge that is held in the rituals from their homelands with the exigencies of their contemporary life. For the 2024 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, Stefanou installed a four-channel video Hym(e)nals, 2022. It depicts young women on horseback from a local pony club. Stefanou has been working with riders, some of whom are neurodiverse, for over ten years. In the series of vocal workshops with these riders she has been helping them extend their communication skills with each other and their horses. Of this process Stefanou states, “I’ve seen horses come and go in the herd, hosted wakes for the deceased, and witnessed teenagers find confidence in their voices under the weight of a complex time. When we first sang together, some found it difficult to produce a single tone—projecting one’s voice is not easy, let alone on horseback. But over time, something shifted. Empowered vocalisations took shape, moving beyond hesitation into play.”

However, rather than conjuring associations with mythological or aristocratic riders, it has a much more mundane focus. The horses are working horses. The appearance of the women on horseback is veiled by a nocturnal filter that debunks the conventional associations but also leads us closer to a silent communion. The deep bond between horses and the love within and across species is also featured in an earlier installation, Wake for Horses, 2021. For this work Stefanou installed a single channel video at the edge of an enclosed paddock. The horses had lost one of their herd. They gathered near the screen, sniffed around the cables, and ambled together.

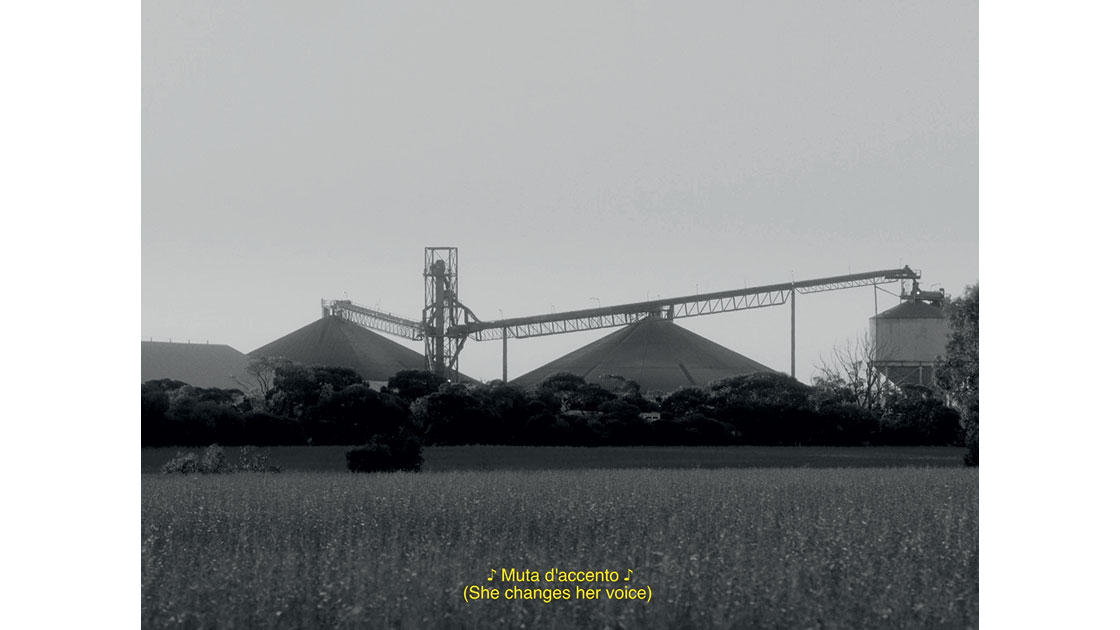

In Grandmother’s Started the Revolution, 2021, Stefanou persuaded four generations of women in her family to pass a red dyed Greek easter egg from mouth to mouth. “The invitation to make this work was rooted in protest against gendered violence, and I couldn’t help but think of the ways violence reverberates through bodies across time. Every member of my family has been affected by male violence—whether through domestic partnerships, state aggression, classism or the weight of patriarchal dominance. Passing an Orthodox red egg through the mouth, sourced from our own chickens at the time, became a quiet yet transgressive gesture—queering the Greek family unit, which is traditionally bound by the passing down of the male name and patriarchal spirituality,” states Stefanou.

In this work the intimacy is self-evident. However, the method of passing the egg evokes a chthonic power of rebirth and summons a pagan symbolism that precedes and exceeds Christian beliefs. Such unspoken connections are still real in the diaspora, and they can even come alive on a red velvet Louis XV sofa. In a number of Stefanou’s videos we see her smiling, listening, leaning into, and drawing from such profound interpersonal exchanges. Through these interactions we get a glimpse into mysterious lines of power. In some instances, the communication is sensorial rather than linguistic. It is expressed as a transmission of care and love and may manifest in the form of healing and stewardship.

Stefanou’s 2022 work, There is a Dead Rabbit Under the Greek Family Unit, is a relatively simple, short video that was shot in Wattle Glen valley. The gum trees, cicadas, and birdsong convey an Australian colour and tone. The video intersperses the habitual preparation of a rabbit for a family meal with an unusual acoustic performance conducted by members of Stefanou’s family. There are close ups of her grandmother’s hand skinning and gutting the rabbit. Stefanou is both recording and learning the art of preparing the rabbit. Some jewels are then stuffed in the rabbit skin. The wider shot reveals a family sitting on three sides of a long table. They are wearing decorated masks that are inspired by the Pontian Greek designs, and which also signify the period of COVID. The table is decorated with bowls and plates that hold jewels, bells, large nuts, blood oranges, cherries, and cymbals. With no particular musical direction each member rustles and jingles the various items on the table. It has a rustic, mystic resonance of an animated tableau—a living and humble version of da Vinci’s The Last Supper, 1495-8. The rustling of bells, tinkering on the cymbal, and rolling of beads sutures the scene with imagined echoes from a village—the slow clambering sound of goats in the field, the domestic chatter, and the ritual chimes that summon the family to gather.

This video work is embedded in the preface to an essay by Stefanou called Peasant Surrealism in the Poor Acoustics: Classed Vocalities issue of the online journal Disclaimer. The essay is a virtuoso piece of writing. It is structured as four short bullet points. Written in a staccato style that is in part inspired by the aggressive manifestoes of the avant garde, and in part an elegiac reflection on the resilience of peasant ideas, values, and practices. The first bullet hits the olfactory glands. It traces back the aristocratic desire to hold the sweet scent of a fig to the production line of perfumes that begin with the intestinal tracts of mammals. A peasant is not afraid of all the smells, sweet and pungent. They can walk through the sharp ammonia in cow’s piss and over the pervasive squelching of rotten quinces.

In the second bullet Stefanou takes aim at the missing chapters of peasant history. They were, as the great theorist Teodor Shanin noted, the prime agents in the communist revolutions and emancipatory struggles, and yet, when the fighting was over the enlightened elites wrote the role of the peasants out of the story. They were slurred, denigrated, diminished, and at best treated as mere pawns in plans plotted by generals and not even named by poets like Lord Byron. Bullet three contrasts the shuddering eros of peasant love with the restrained etiquette and puritanical comportment of the aristocracy. In this crossfire we witness the difference between a bitter-sweet passion that devours and cares in equal strides, with the love that only speaks its name in double negatives. There is ecstatic elation on the one hand and then there is that other life, the one that is condemned to polite petrification and stultified sexuality that was so delicately exposed in The Shooting Party, 1984 (directed by Alan Bridges).

The final shot in bullet four is ambivalent, what happens to the peasant who has made it? How do they cope when their life of scarcity is overtaken by surplus? In the village meat was eaten during festivities. Then in the city it is on the table every night. Clogged arteries and obesity arrive. The urban peasant looks down and cannot see over his protruding belly, he turns to his brother and asks: “do you need a mirror to see it?”

Stefanou begrudgingly celebrates the pleasure of excess, with reference to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, she says: “what is the point of denying myself what they (the white bourgeoisie, the real bourgeoisie) have given to themselves and each other?” But above and around this sated feeling is the guilt of gaining access to stolen lands. The essay is making visible aspects of a culture that was on the verge of extinction, and which, despite the slurs cast upon it by the elites and its marginalisation through the machinations of modernity, has survived in the diasporic consciousness of Stefanou’s family.

The final scene in There is a Dead Rabbit Under the Greek Family Unit shows the family performing a traditional Greek line dance. The elderly members move neatly in rhythm. They take the lead and wave their free hand with confidence. The younger members follow. Their movements sprightlier but slightly out of step with the tune. Dancing is a bonding experience, and here the flow of energy is uneven. The front and back end of the dance line remain linked, but there are awkward lurches and out of sync steps. Such small goofy steps are suggestive of the cultural gaps. The movement of the younger members evoke a desire to be close, but their steps are not as accustomed to these tunes. In short, they have not danced enough to make it flow. Even with their backs turned to the camera we can sense that they are dancing with a mixture of joy and duty, but in the collective smile there are broken and missing teeth.

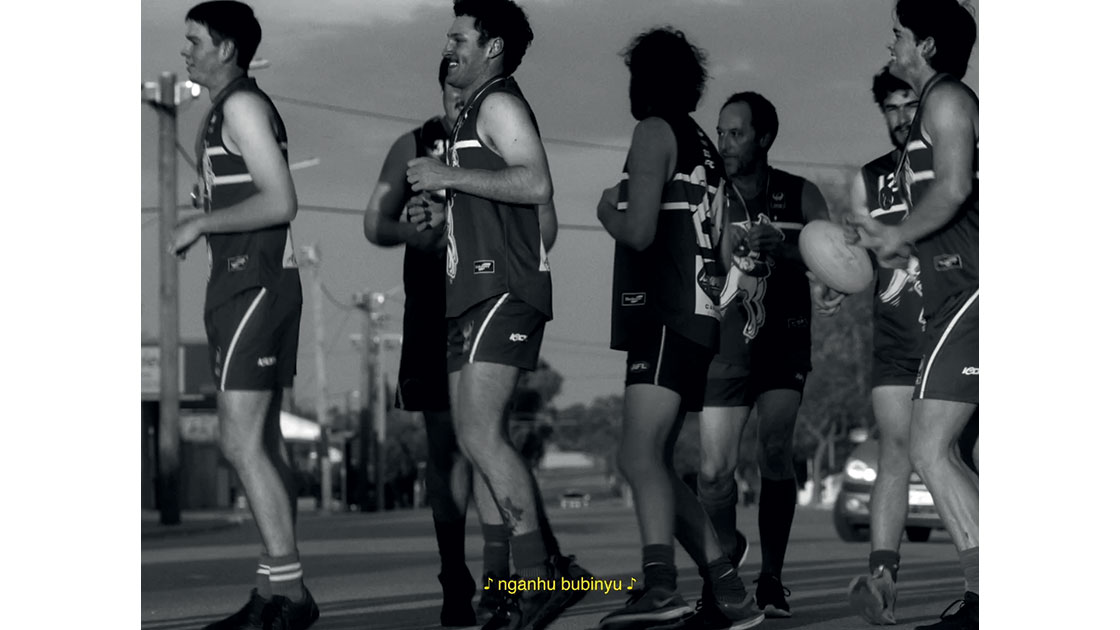

A second project that came out of a sustained engagement with people in rural areas extended her understanding of the challenges of stewardship and interspecies companionship. Over a year-long residence that commenced in 2022 Stefanou worked with wheat and wool producing farmers as well as the wider community in the rural town of Carnamah in Western Australia. Stefanou immersed herself in this remote community in order to gain understanding of the value that the local farmers gave to wheat and wool, and then trace the trade of their product across the sea routes to Southeast Asia and other parts of the world. Stefanou hung out with farmers. Catching rides on their tractors. Listening to their stories. Noting their aspirations. And trying to connect the dots.

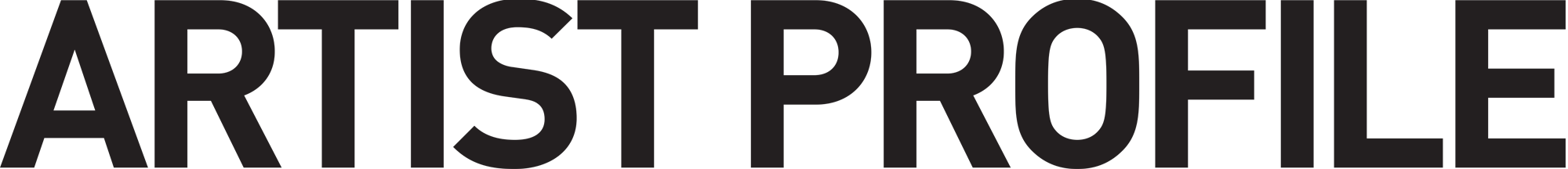

On the night of the Australian referendum in 2023, where the nation was asked to vote in relation to the proposition of including an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, Stefanou organised an event called The Ball, 2023. Stefanou was deeply aware that the majority of the community was not in favour of supporting the referendum. There were many reasons why people voted against the inclusion of an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. There were Indigenous groups in Western Australia who believed that their leverage in politics was best secured at a local and not at a national level. Among many immigrant communities there was resistance on philosophical grounds of equality. Many well-meaning lawyers argued that the constitutional amendment was confusing and contradictory. The prominent Indigenous activist Gary Foley was opposed to it, because he suspected it was always doomed for failure, and that it promised too little too late. Not everyone who voted “No” was a racist. For the public event in Carnamah, Stefanou invited children, working-class poets, farmers, footballers, and local artists to come together to reflect on place and space. They gathered at the local town hall, a venue only periodically used—there has been no ball there for over fifty years. The performances were recorded in a single channel black and white video.

The most ambitious outcome of this residency was the performance and video called Back-Breeding, 2023. The term back-breeding refers to the process of breeding livestock to revive recessive and disappearing traits. In this project Stefanou conducted vocal workshops and followed the practises of local farmers. She outlines this process, “I met the sheep that contributed to the artwork and their shearers. I stitched the tractor’s costume for ten days straight in 45-degree heat with my collaborator, Donna Franklin—sweat, fibres, and the raw animalness of production making my eyes water. Wil Normyle and I ran around drought-sunken crops to find the perfect filmic moment, learning how to drive large tractors on the spot. And then there was the singing: intergenerational voices from across the region, from landowners with vast swathes of land to those moving to the mid-west after being priced out of the city.”

It is a metaphor for the need to enhance resilience in the time of climate change by connecting past strengths to contemporary challenges. Stefanou reflects, “All I did was stay long enough to witness what was already there—the performative potential embedded in agribusiness life, its absurdities, and its tenderness, and the way class and inter-species labour are obscured and nullified within middle-class-dominated spaces, such as the arts.”

She was drawn to the rough textured richness found in large bales of wool and also the austere force and pivotal function of the tractor. John Berger, who produced the most endearing and enduring portrait of the life of peasantry in his book Pig Earth, 1979, argued that the tractor was the most powerful symbol of the end of peasant life. The tractor signified the end of back-breaking manual labour but also the beginning of industrial farming practices. It is a mixed blessing, and as bitter as this pharmakon is, no one would farm without a tractor, not even in the village of Quincy where John Berger spent the second half of his life. In tribute to this tractor as the new “beast of burden” Stefanou staged a series of portraits of the tractor adorned with a thick coat of raw wool. Stefanou’s grandfather was tragically killed when a tractor overturned on the family farm in Wattle Glen. The human figures in the foreground salute and sing to this creature with awe, but the viewer is left with a disjointed image—a hybrid world of animal and machine with humans dependent on both.

These are important contributions not only towards the expansion of the field of art but also in the national and global conversations on the transfer of cross-cultural knowledge and dialogue on environmental stewardship with Indigenous communities. The legacies of European colonialism, the imposition of industrial farming practices, and the more recent neoliberal commodification of social and cultural relations have devastated communities, left vast tracts of waste land, and mutilated the human sensorium. If we are to reverse some of this damage, we must first find new starting points from which we can build positive connections. No dialogue operates in a one-way stream. It requires both listening to others and discovery of a voice from within. The archive of Western knowledge must therefore be revisited. There are some forms of knowledge that perdured the violence of colonialism, industrial modernity, and the neoliberal state. Stefanou has drawn on her uneven grasp and reception of “peasant surrealism.” This offers a vital starting counterpoint to the new world order. There are more cues and clues in how this conversation can be extended. A closer attention to peasant farming in the West may be one of the most fertile sources. All peasants knew that the land was a finite resource. It required deep care. There were fallow seasons, when the fields were left to “sleep.” A copse was always maintained, and in the wild bush and among branches of the big tree, foxes and birds hid. The roots of this tree also kept the salt line lower. Peasants knew how to plant one species next to the other to ensure that nutrients were recycled. They kept fields fallow and were permitted to glean the leftovers.

These terms that were in the centre of a peasant imaginary—copse, fallow, gleaning—are also interwoven within ecological practices and a cosmological worldview. At the core of this worldview is a modest self-awareness. An appreciation that the majesty of the cosmos and the grace in little gestures were somehow interlinked. My friend David Pledger, the artist and writer, argues that an artist in the twenty first century can no longer be confined to being either a descriptor or even a critic of society. Those elevated and detached positions are not sufficient. The challenge of our time is to both be engaged with communities and to be at the forefront of positive change. The artist must be a protagonist. They must make the world that they wish to inhabit. I agree. To make this new world, we must also resurrect and retain some parts of the old world. To this end the work of Stefanou offers us a marvellous entry.