Ildikó Kovács | The Infinite Line

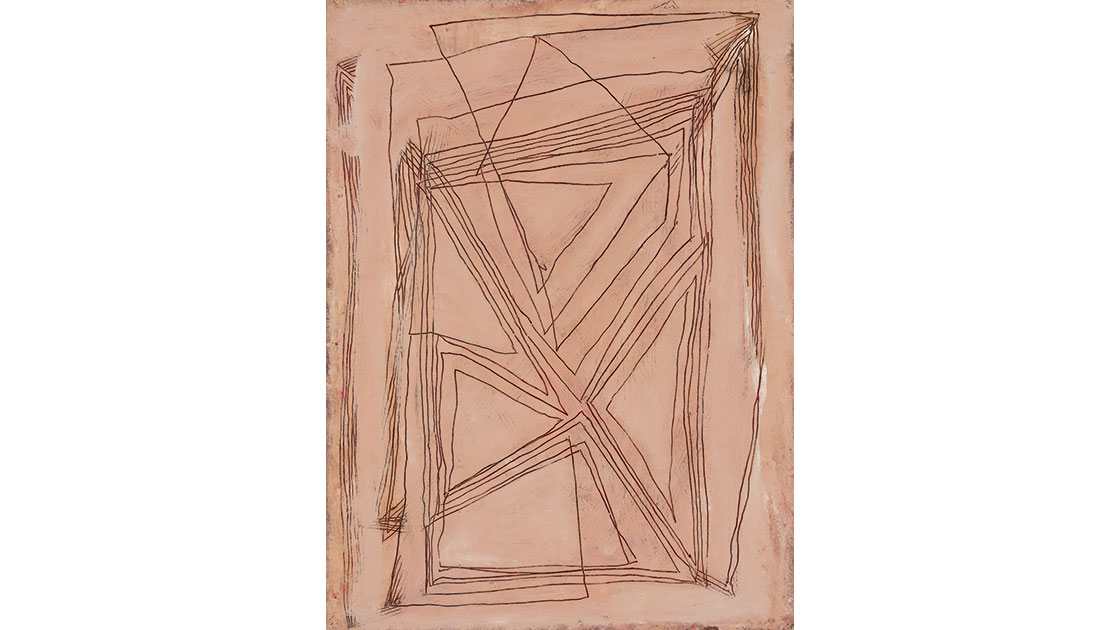

Ildikó Kovács, an Australian artist known for her visually striking abstractions, has just returned to her studio at Bundeena, south of Sydney, after time away on the island of Lombok, Indonesia. She’s rejuvenated and anticipating the resumption of her painterly dialogue with the materials of her art. She predicts that the atmospheric wet season’s light and lush green rainforest tones will feature soon.

Kovács was born in Sydney, a first generation Australian from immigrant parents fleeing war-torn Hungary. Her upbringing was very much as part of the Hungarian diaspora. Homelife embraced traditional food and music, and Magyar embroidered motifs. The stories told were often melancholic with a longing for the life and loved ones left behind. At age eleven, Kovács lost her father.

By age seventeen she was at art school (1978-1981), firstly St George College, then the National Art School. It was a revelation. Painting’s arrival precipitated healing and forward movement into the world. A period of travel in Europe followed, soaking up works filling museums and galleries across the continent. Kovács has acknowledged the influence on her artistic development of abstractionists such as Willem de Kooning, Tony Tuckson and, in his pre-figurative era, Philip Guston.

Works in museums and private collections are endpoints, marking the culmination of artistic processes. But what drives Kovács is an interest in process itself through a series of conjectures or material dialogues. “Intuitive” is a frequently heard adjective in discussions about her work. You could say her praxis was not a conscious choice; instead, perhaps it chose her as a medium.

Kovács describes her early work as “busy and energetic”—painting in a speculative and experimental manner with youthful exuberance full of expressionistic fervour. She explored the use of a variety of surfaces and media, and incorporated sculptural elements, adding physical depth while developing techniques of layering and reworking. In combination with her skilful use of colour, she was building complex images evoking emotional responses, her abstraction opening spaces for visceral engagement.

This was followed by a period of intense questioning and searching for meaning. It drove her processes into multiple cycles of layering and reworking, resulting in more minimalist palettes. Seemingly, the propositions put forward were unresolved and the dialogue one-sided. Then, in the nineties, forms began to take shape, and a new motif emerged: the line. This led to what she identifies as “breakthrough works;” the line also became a metaphor for the nature of the artist herself.

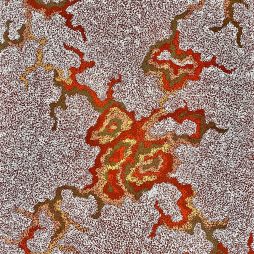

In the mid-nineties Kovács spent time in Broome. This was to have profound significance as she discovered the Kimberley landscape, embracing its Australianness. It led her to increasingly question her European heritage and, in so doing, brought forth something deeper. Although working in quite a separate way within the broad field of abstraction, observing the way Indigenous artists painted during several visits to remote communities, their naturalness with paint and lack of inhibition resonated strongly with Kovács.

The emergent line in Kovács’ work was no simple boundary. The line became more than an artifice of abstraction, instead developing into a complex story-telling device capable of capturing an extended reality. The line, used to sculpt the space of the picture plane, emerged as a multi-dimensional and vibrantly textured visual artifice. Her work was now imbued with a symphonic force.

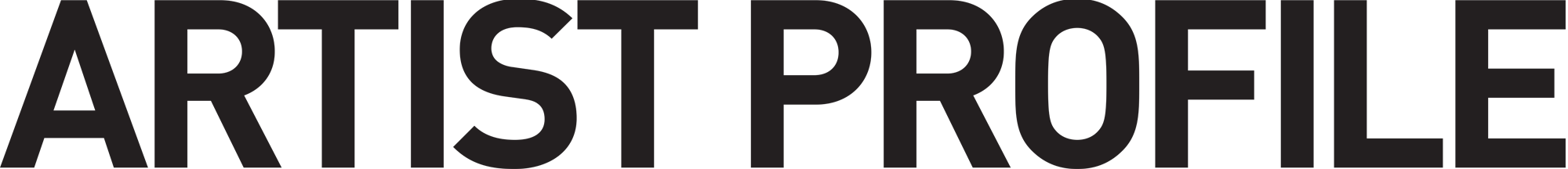

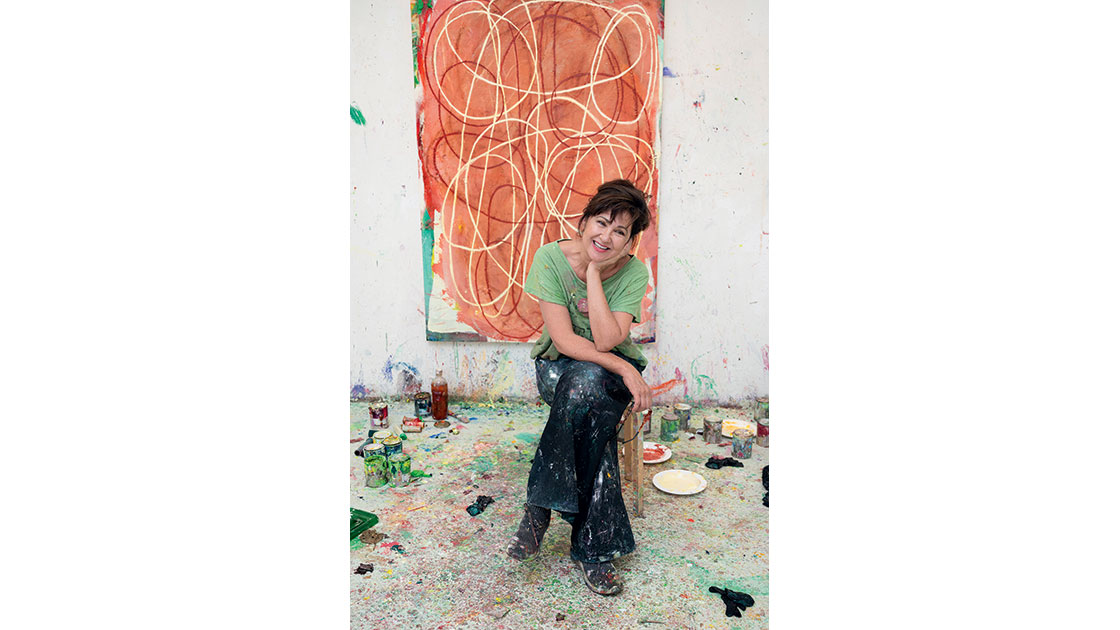

Even deceptively uncomplicated renditions of the line as seen in Sloe Roam, 1995, and Cat’s Cradle, 2018, carry ambivalent tensions between serendipity and purposefulness as they trace their paths through time and space. But the process was a complicated one of oil paint smeared by hand and brush, and lead pencil and wax pencil engraving lines into oil paint. Indeed there is a resonance in Kovács’ evocation of the line that connects with fundamental cosmic principles. In the catalogue essay for Kovács’ 2019 travelling exhibition The DNA of Colour, curator Sioux Garside equated the linear renditions with both the spiral nature of DNA and gravitational ripples coursing through the fabric of the universe. Kovacs’ work can be interpreted as like a scientific investigation attempting to unravel and map the nature of reality.

The engaging dynamics of colour and form in Kovács’ works belies the incredible physicality that goes into their creation. Mt Warning, 1995, a large work over two-by-two meters “almost drew blood” because it took endless reworking of the board using litres of turpentine, a process that can take days or weeks before the line even emerges. It was then choreographed intuitively; the result revealing a tectonic dance of the ancient volcano through countless millennia. Similar energy underlies other works. With Jibbon, 1998, the line traces a multidimensional range of concentric circles in the forest canopy. Whereas with Cockatoo, 1993, the flocks with their familiar sulphur-coloured crests appear enmeshed throughout a metaphysical ecological range. The work captures their relationships, not their reality.

From around 2008 the line developed texturality when Kovács experimented with the roller. The line had become a living entity with this new trajectory; it now had character and voice. Her most recent works have become even more complex compositions that capture a vision of relational interactivity between people, the more than human world and place.

Often, names for these works will not suggest themselves until after completion. For example, Acacia, 2010, is a work that seems to evoke a new green world of chlorophyl and chloroplasts, the end point of a long physical process. A name for a painting may be suggested when observing the swaying movement of seaweed while swimming near her studio, or seeing trees twisting in the wind in the Royal National Park, New South Wales. Bush, ocean and the linearity of the far horizon are constant companions.

As has been noted elsewhere, Kovács has developed mesmeric skill with colour; Over the Gap, 2015. has a nuclear hum of vibrant central desert colour. What has grown from the artist’s questing dialectic over the years is a distinctive relational ontology of being inspired by a clarity of vision of the Australian landscape. It reflects and encapsulates diverse embodied and emplaced experiences with a sense of the deep interdependence of people and spirit. It explores existential places beyond the physical and has all been built through painterly intuition. As Kovács says “. . . a good day is when everything is synchronised. The work paints itself.”

There is a sense that the line still has a long way to travel, and there will be many more good days ahead.