PROFILE: Mason Kimber | The Skin of the Painting

Mason Kimber’s newest paintings mark the artist’s furthest explorations yet into what he describes as “spatiality in painting.” Ahead of his first institutional solo exhibition, Kimber reflects upon a half-decade of work that draws together informal currents of materiality, haptic visuality, place and memory.

At his Leichhardt studio, Mason Kimber shows me a cache of photographs taken of a Perth nightclub, owned by Kimber’s father, in the 1980s and 1990s. The club had many names and many looks—including a Bat Cave and a Shark Bar—all designed from his father’s outsized imagination. Kimber remembers being taken to the club by his father during daylight hours, seeing the days-before and mornings-after of a place only known to its patrons in the darkness.

An image of a ladder on a clad, textured wall revives Kimber’s childhood memory of climbing to reach the club’s DJ booth. Now an artist drawn to the creation of similar surfaces made of modelling compounds and extruded polystyrene—and a DJ himself to boot—it is difficult not to psychoanalyse and read deterministically Kimber’s creative life through these records of formative encounters.

Drawings derived from these photographs and memories are pinned to the studio walls. They are not representational sketches of the club, nor even compositional rehearsals—for Kimber, drawing is instead a way of “homing in on the spatial dynamics of a surface.” What that space is inhabited by and constructed from—light and shadow, weight and lightness, interior and exterior, movement or stasis—remains open to Kimber’s process.

I ask if Frank Hinder is a possible influence, thinking of the spatial push and pull in his depictions of metropolitan Sydney (as in Kaleidoscope Tram, 1948). Kimber replies that Godfrey Miller is closer to hand, though with differing commitments to “compositional scaffolds” and handling of the numinous. Nearer still, perhaps, is Elwyn Lynn, whose attention to materiality, textural surfaces and general informality is on a wavelength similar to Kimber’s own.

In August, an exhibition of Kimber’s recent works made between 2021 and 2025 will be on view in A Caressing Gaze at University of New South Wales Galleries, Sydney. The show’s title is drawn from film theorist and philosopher Laura U. Marks whose work Kimber incorporates into his nearly completed doctoral thesis. Marks—in her book The Skin of the Film, 2000—draws on the work of prior theorists (Aloïs Riegl, Henri Bergson, Gilles Deleuze) to define twin concepts of “optical visuality” and “haptic visuality” in cinema.

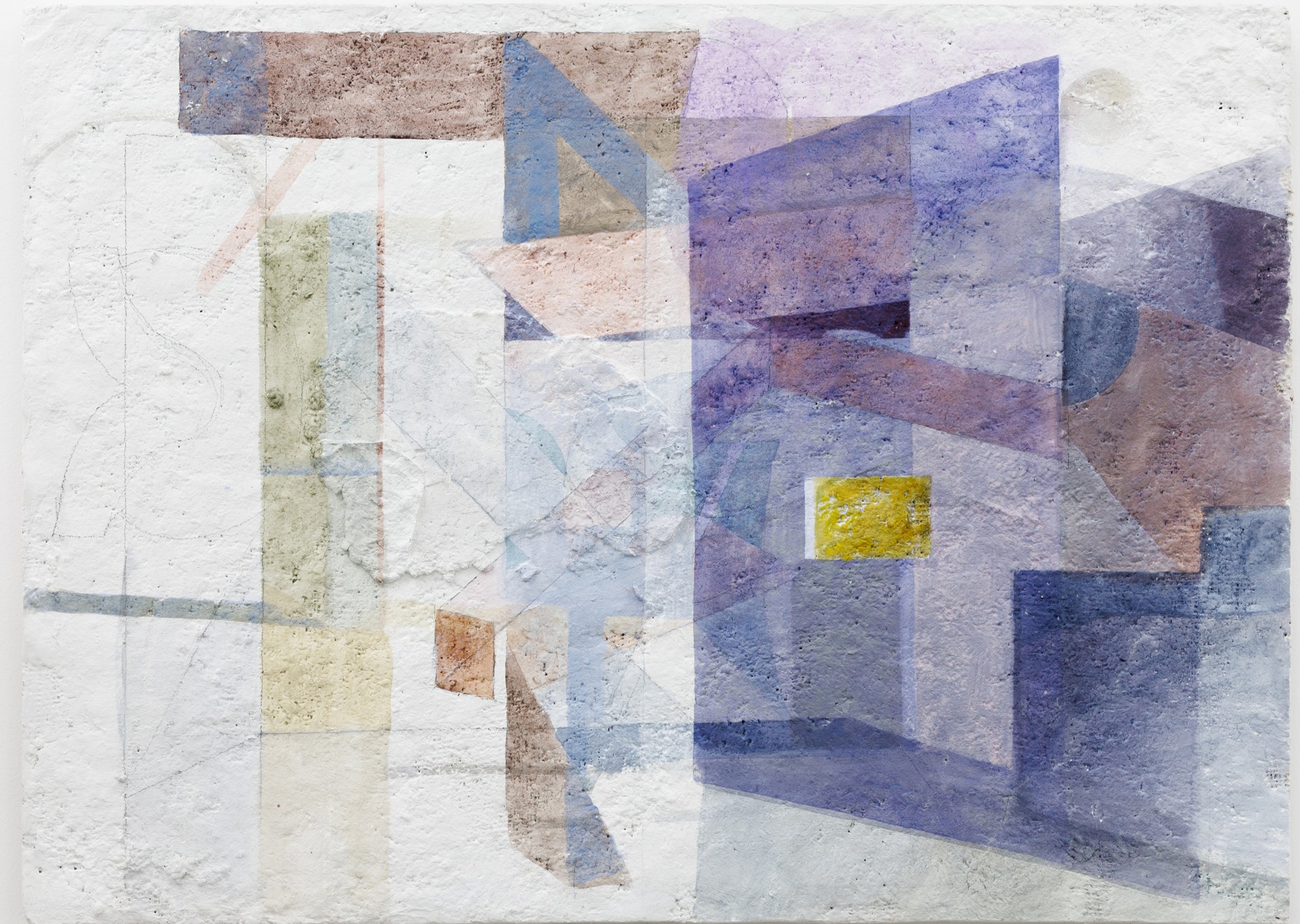

Strata (Blue), 2021, acrylic, gypsum, compost render extruded polystyrene, wood, 60 x 45 x 5 cm

Optical visuality refers to the idea that the visual cues of images are sufficient in themselves for an audience to comprehend them, as in most narrative films. But a more complex function of cinema is where images are interpreted by senses other than sight. Marks describes haptic visuality as one such example, where “the eyes themselves function like organs of touch.” Kimber is drawn to this idea, in particular Marks’s note (also from The Skin of the Film) that haptic visuality “is more inclined to move than to focus, more inclined to graze than to gaze.”

Haptic visuality in painting is an established concern. Marks refers to Dutch still life as an example from the visual arts where the eye is left to skate across an array of surface effects—the pocked rind of a lemon, the slime coat of a fish; cool, polished silverware, or silken fabrics—in addition to or, at times, in place of substantive forms. It is a specific example of a tradition that involves, as Marks puts it, “intimate, detailed images that invite a small, caressing gaze.”

Tactility, surface and place have formed a dominant part of Kimber’s practice over many years. While visiting his wife’s family in the Philippines in 2018, Kimber made his first use of silicone moulds, made from pressing a malleable putty into architectural surfaces around Quezon City. From there to his Strata works, 2021, and casts made from the colonial fixtures around the National Art School—where he completed his master of fine arts and continues to teach—mould-making has become essential to Kimber’s practice. With each casting—supported by chance interventions in the pouring, breaking and recontextualising of each fragment—these negatives of surface textures can draw direct, situational and narrative connections between mould, cast and artwork.

But Kimber’s newest works are distinct from prior series in that the “origins” of his moulds have become incidental. “I’ve come to embrace the alchemy of the studio,” says Kimber, “like a witch’s cauldron.” Cast fragments, now, are more “like a memory” than an index—a fitting evolution to contend with the challenge of connecting spatially with his father’s long-since closed nightclub.

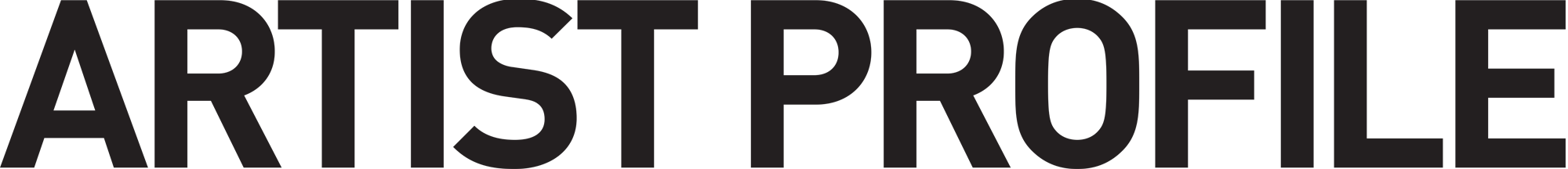

Tablet / Glare, 2023, acrylic, gouache, composite render, extruded polystyrene, wood, 82 x 60 x 6 cm

Kimber is a painter, though since mould-making entered his practice, it is arguable that either sculptural relief or abstract painting has stood forward in any given work or series. In his recent Tablet works, 2023, there is more of a shared stage for these elements—with relief acting as a frame for abstract paintings concerned with the behaviour and quality of lens flares and other light effects.

In his latest works from 2025, Kimber has solemnised this “marrying of painting and relief.” Where earlier works had alcoves for fragments to nest, or frames that housed painted surfaces, like frescoes in a cathedral, entire surfaces are now relief and painting together. Kimber makes his supports by hand from a range of materials, including hessian, paper pulp and plaster. Like the lunar surface, there are craters where mould-cast fragments used to sit before being removed by the artist. These indefinite, untraceable absences have been (not without violence) excised and blurred over, like the tide washing over footprints in sand.

Skyfade, 2025, acrylic, paper pulp, hessian, composite render, extruded polystyrene, wood, 92 x 80 x 7 cm

Over the pocked and varied surface of this material topography, reliant on the preparatory mapping undertaken in his drawings, Kimber paints. The “spatiality in painting” that results is more abstract than the reckoning of translating the world of three-dimensions into two practiced by representational artists. Instead, it is a way of getting at surface by seeing it in haptic terms. The eye may, momentarily, settle upon a divot or a bump for contemplation, as it might over a passage of colour or an exposed pencil line—but the space within and of each painting is kinetic, and the feedback with the viewer highly tactile.

All artists want the attention of a viewer, but few artists articulate in their work the conceptual basis of that attention. Kimber’s paintings relish in each articulation of haptic visuality, inviting us all to brush against the textural and material world of surface—much as the eyes of a certain child might have done when surveying the nightclub created by his father over thirty years ago.

Exhibition:

Mason Kimber: A Caressing Gaze

29 August – 16 November 2025

UNSW Galleries, Sydney

Images courtesy of the artist, UNSW Galleries, and Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

Jack Howard is a Sydney-based writer. He works for Parallax Legal and Annette Larkin Fine Art.

This article was first published in Artist Profile Issue 72