REVIEW: French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The hoary old question, “Is it Monet or Manet?” is well answered by the current exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. There are some great Édouard Manets (although strictly speaking he was not an impressionist), and a myriad of stunning Claude Monets. Other luminaries in over 100 paintings and prints include Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Mary Cassatt, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and impressionism’s precursors, notably Eugène Boudin.

Divided into ten thematic sections, the curatorial brief (according to the NGV’s online publicity) is to place “emphasis on the thoughts and observations of the artists themselves.” And, to this effect, texts proliferate but do not dominate. But French Impressionism does not need to take recourse to artists’ intentions. The works, dare I say it, speak for themselves. Although considered radical and subversive in their time, and rightly so, their preoccupation with the nuances of French modernity, on the one hand, and the charms of the country and the beach on the other, now attract admirers in droves.

First opened briefly in 2021, French Impressionism was dramatically cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic. Four years later, and now safely ensconced in the NGV, the Boston Museum of Fine Art’s enviable collection of impressionism offers an extraordinary insight into a critical moment in western European culture. The NGV exhibition ranges from a comprehensive assembly of beach scenes by Boudin to canvases lavish in colour by Renoir, from Monet’s landscapes and seascapes to Pissarro’s peasant women and Cassatt’s opera boxes. There is only one work by Gustave Caillebotte, a cunning painting of a fruit stand, but his sexually provocative Man at His Bath, 1884, also held by Boston, has stayed home. Its presence here would certainly have thrown into question what impressionism is all about. That said, the exhibition does make one think carefully about the integrity of this stylistic label.

In rooms carefully curated to re-imagine “nineteenth-century residences of East Coast collectors,” thematic narratives include early impressionism, the seduction of water, studio dynamics and the aesthetics of neo-impressionism. Boudin is well-represented by small, intimate beach scenes, including his best-known Fashionable Figures on the Beach, 1865, an oil on panel showing smartly dressed women and men; some standing, some seated and others bathing. A vast blue sky with a smattering of clouds fills two thirds of the picture. This is an image of gentrification in which the seaside simply replaces the boulevard.

I was struck by Theodore Rousseau’s Pool in the Forest, early 1850s, where there is something strangely sinister about this dark, idyllic scene of trees, water and cattle. Meanwhile, Monet’s Woodgatherers at the Edge of the Forest, c.1863, has two Millet-like figures set against a partially sunlit, woodland. Jean-François Millet is represented by, amongst others, End of the Hamlet of Gruchy, 1856. Born in Gruchy, a village near Cherbourg, Millet depicts an aproned woman with a child in a peaceful scene outdoors; But there is something menacing about the tree the child seems to want to touch—it dominates the picture with its sinewy silhouette.

Berthe Morisot, White flowers in a bowl 1885, oil, canvas, 46.0 x 55.0 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of John T. Spaulding. Photographed, copyright, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

Engaging still lifes by Berthe Morisot, Paul Cézanne, Gustave Courbet, Henri Fantin-Latour and Gustave Caillebotte fill the fourth room called “In the Studio.” Morisot’s spirited White Flowers in a Bowl, 1885, with its creamy blues and whites contrasts with Cézanne’s rock-hard Fruit and a Jug on a Table, c. 1890–94. Fantin-Latour’s Flowers and Fruit on a Table, 1865, a consummate piece of trompe l’oeil, gives way to tactile joy in his Roses in a Vase, 1872, and Roses in a Glass Vase, 1890. Courbet’s Hollyhocks in a Copper Bowl, 1872, by contrast, shows the flowers as sluggish and flabby in a painting verging on the anthropomorphic. Courbet, it should be said, never once exhibited with the impressionists in any of their eight group exhibitions from 1874 to 1886. His inclusion in French Impressionism is both strategic and pedagogic—stretching Boston’s brief and attracting inquisitive publics.

Paul Signac, Port of Saint-Cast, 1890, oil, canvas, 66 x 82.5 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of William A. Coolidge. Photographed, copyright, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

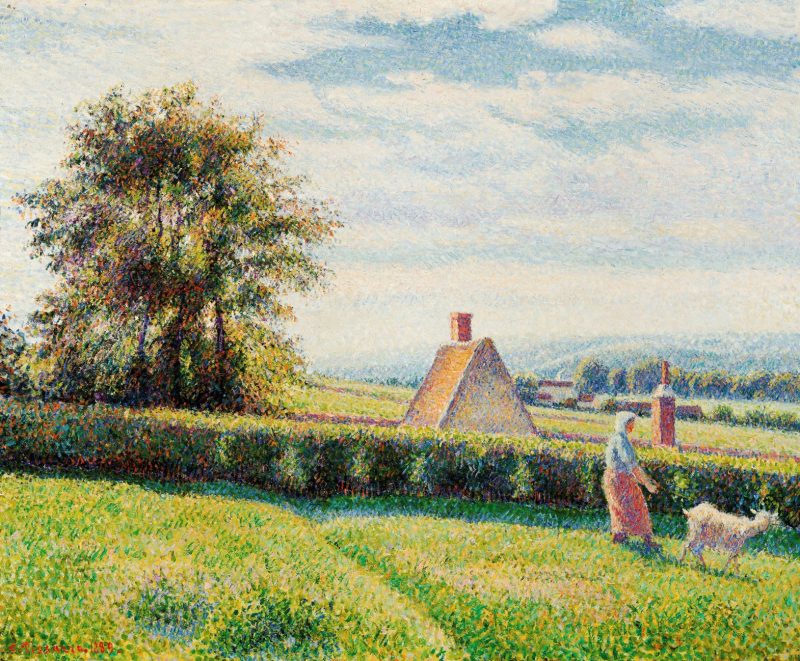

Paintings by Pissarro, Sisley and Paul Signac dominate the sixth room and provide insights into what came to be known as neo-impressionism or divisionism. Distinguished by dots or “commas” of paint, this approach is seen to great effect in Signac’s Port of Saint-Cast, 1890, and Pissarro’s Spring Pasture, 1889. In the former, the shimmering, speckled surface is divided horizontally into stretches of beach, sea and sky, while in the Pissarro a single peasant woman with a sheep walks in a bucolic, sunlit pasture. Conversely, Signac’s claustrophobic Gasometers at Clichy, 1886, in the NGV’s own collection, shows this north-western suburb of Paris taken over by industrialisation.

Camille Pissarro, Spring pasture, 1889, oil, canvas, 60 x 73.7 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Deposited by the Trustees of the White Fund, Lawrence, Massachusetts. Photographed, copyright, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved

The impressionist prints that come towards the end of French Impressionism include rather scraggy works by Pissarro, Degas’ stunning Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings Gallery, 1879–80, showing a stylish Cassatt, umbrella in hand, looking at pictures, and Cassatt’s In the Opera Box (No. 3), c. 1880. Persuaded by Degas to take up printmaking and contribute to the art journal Le jour et la nuit, a magazine that was never published, Cassat produced fifty impressions, showing a solitary woman holding a large fan and sitting assuredly in a loge.

A run of small photographic portraits of the artists represented in French Impressionism concludes the exhibition. Taken by the famous Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), they put a face to the name. More revealing, and delightful, is the short silent film of a portly Monet, with a swagger and cigarette in mouth, painting in front of his water lily pond in Giverny. Shot in 1915, when the artist was seventy-four-years old, it’s an excerpt from Ceux de chez nous (Those of Our Land), directed by the controversial film actor and playwright Sacha Guitry. If we could hear Monet speaking, he might be saying in his typically unassuming way “I’m not performing miracles, I’m using up and wasting a lot of paint.”

Exhibition

French Impressionism from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

6 June – 5 October 2025

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Images courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and National Gallery of Victoria Melbourne.

This article was first published in Artist Profile Issue 72.