The vision of Emily Kame Kngwarreye

There is an air of anticipation for Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s first large-scale exhibition in Europe, to open at the Tate Modern in London this July. Kngwarreye’s compelling work, made in the remote Utopia region of Central Australia, will travel to the shores of the Thames—a climate, audience and geography another world away. In this European context and Western institution, the stage is alight with questions and debate on how Kngwarreye should be framed and understood as the visionary that she was.

Led by curator Kelli Cole, Emily Kam Kngwarray at the Tate is a continuation of the retrospective Emily Kam Kngwarray: Alhalkere—Paintings from Utopia curated by Cole and Hetti Perkins at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in 2024.

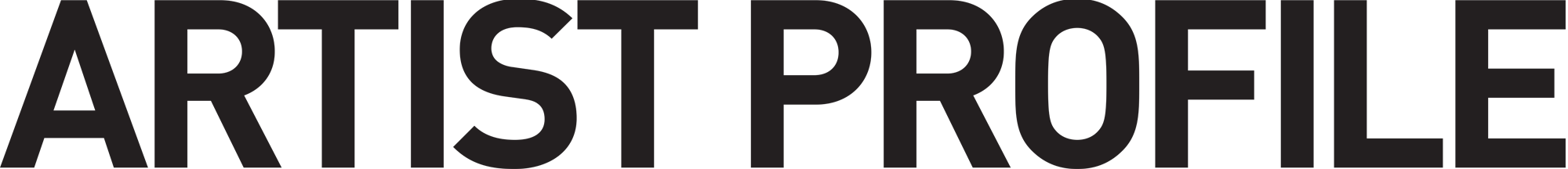

The lasting impact of Emily Kame Kngwarreye (c.1910–1996) on the international art world has been great despite her short career. Beginning painting at the age of seventy-seven, in the last decade of her life Kngwarreye created over 3000 works, averaging one a day. This creative momentum was built throughout her life, as Cole explains, “Kngwarray’s art wasn’t a new beginning; it was a direct continuation of her lifelong cultural practices. Everything she painted was rooted in her prior experiences and cultural knowledge.”

For those who have been privy to the rhythmic, pulsations of her batiks and paintings, her work is celebrated for having a living presence. Long-standing art dealer of Kngwarreye, Christopher Hodges, places it down to the unique vision of Kngwarreye that aligns her with the modern masters, “Emily had the holistic vision of what it was to be a part of this land Alalgura and part of this continuum of life. In her mind it was ‘the whole lot’.”

The distance from Australia to London has defined a significant shift in the Tate exhibition and the work originally displayed in the NGA retrospective. The Tate will include new artwork sourced from private and institutional lenders across Europe and North America, including from the Albertina Museum Vienna, Austria. Australian gallery, D’lan Contemporary, listed in the Tate Supporters Circle, has provided significant support, assisting in the sourcing of art from private lenders in Europe and Australia. The ongoing support of the commercial world to the sourcing and transport of the artwork is a vital part to the success of this exhibition.

As with all great artists, Kngwarreye’s oeuvre and how she should be framed sparks conflicting views. The irresistible pull of her work has resulted in powerful responses, each informed intuitively by the beholder’s background—whether Indigenous Australian, Western canon, or Japanese. Even at the time of writing this essay there is division on how to spell her name—Emily Kame Kngwarreye as spelt by the Art Gallery of New South Wales or Emily Kam Kngwarry as defined by the NGA in the 2024 retrospective.

Kngwarreye’s first international solo exhibition was in Japan in 2008, curated by Professor Akira Tatehata and chief curator Dr. Margo Neale, National Museum of Australia. As the first international curator to present her work, Tatehata framed Kngwarreye as an “impossible modernist,” comparing her to great post-war masters like Jackson Pollock, Brice Marden and Yayoi Kusama. It is in this term that he captures the complexity of trying to frame Kngwarreye, and the universal appeal of her work that seemingly defies singular definition.

In his presentation to the National Museum of Australia in 2008, Tatehata’s comparison of Kngwarreye with three diverse Abstractionists Pollock, Marden and Kusama, demonstrated the impressive depth of her work—able to be compared with a broad range of Abstraction.

Tatehata’s comparison of Kusama and Kngwarreye brought together two different artists, from different cultures and different forms of Abstraction, but whose work share a holistic world view. He noted that in Kusama’s net and dot paintings she doesn’t distinguish between myth and reality, and similarly in Kngwarreye’s dot paintings she didn’t distinguish between Dreaming and her life. They were, as she explained, the “whole lot.”

In his essay for the NGA exhibition catalogue, Stephen Gilchrist examined the complexity of framing Aboriginal art within Western definitions and argued against positioning Kngwarreye’s work within the Western art canon and values of greatness. Rather he called for “a new set of questions, a new set of cultural coordinates and new ways of responding.” However, within this call to action there is no clear path put forward by Gilchrist.

Presenting Kngwarreye to European audiences at the Tate, Cole stresses the importance of explaining terminology clearly and contextualising her as an artist and where she came from. “While viewers might initially perceive her works as abstract, our aim is to encourage a deeper understanding of Kngwarray’s painting beyond the confines of Western art history. We want them to see her as more than just another artist in that Eurocentric ‘Abstract’ canon,” she states.

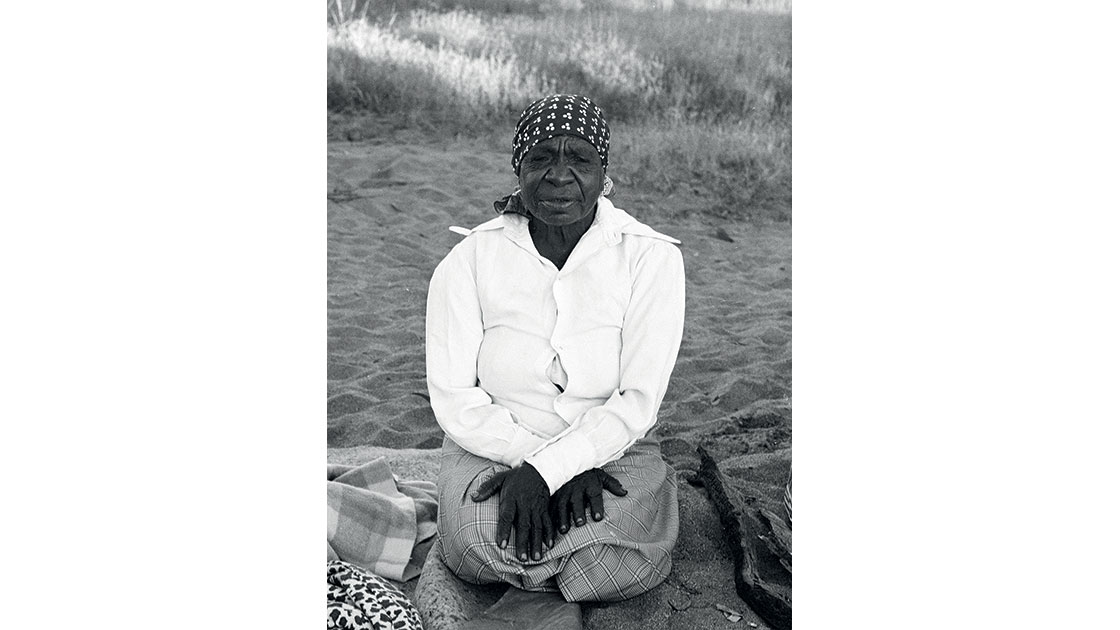

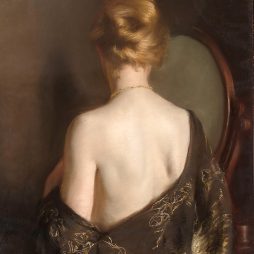

Cole draws attention to the iconography and figurative elements in Kngwarreye’s paintings that distinguish them from being compared to the Western movement of Abstraction. “When looking at Kngwarray’s painting, you need to understand that the lines are not abstract markings, but lines applied with intention. Her paintings, directly reference the application of body paint during awely, women’s ceremonies (song and dance). Where ochre is applied to the shoulders and across the chest and breast; the lines on the canvas echo the lines traced upon the skin of the women.”

Like Tatehata, Hodges embraces the comparison of Kngwarreye alongside other modern masters, particularly Abstraction, outlining, “the paintings are full of meaning. Emily was fully informed by the real and conceptual world, non-abstract things, but she was also a creator of the holistic belief that everything could be summed up in a painting. Just as a casual viewer walking past some of Pollock’s paintings could say there are figures in there, and in some of Emily’s you can see patterns that could be maps or roots.”

Within the post-industrialist walls of the Tate the stage is a Western institution, and in this space sets a challenge to immersing new European audiences to the world of Kngwarreye and the Anmatyerr philosophies and values that she worked to.

The exhibition will include footage of her living relatives doing emu awely (song and dance) at Alhalker. “After watching the film, and as you enter the other galleries, you continue [to] still feel the rhythm and energy pulsating from the paintings that you are standing before” states Cole. “The challenge for me as the curator is to make sure the audience understands the depths of her work and appreciates it.”

The Tate exhibition presents a significant opportunity for Kngwarreye to be recognised as an artist within her own culture and celebrated alongside master artists in the Western canon. In this quandary of debate about how she can be interpreted, Tatehata’s term the “impossible modernist” returns as an apt expression. Whilst Emily’s life and art was isolated from the West and outside world, shouldn’t this complexity be embraced and examined rather beaten down into a singular viewpoint? Ultimately what will be clear is Kngwarreye’s reception at the Tate, as an Australian artist, and the magical quality of her work has proven that it can mean many things to different people.