REVIEW: Are we not all colonisers and migrants?

Birds in Far Pavilions is the first survey exhibition of Pakistani, now Melbourne-based artist Nusra Latif Qureshi, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Her work chronicles and reflects on the journey from her country of birth to observations about her life in Australia.

The story of humanity or modern humans (homo sapiens) is explained by various creation myths across different religions and cultures. Many of these myths have striking similarities with the story of Adam and Eve. For instance, the three great monotheist religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, each hold that man and woman were created by their God. In Norse mythology, the first two humans, Ask and Embla, were given life by the gods Odin, Vili and Vé, who found two tree trunks on the beach and breathed life into them, creating the first man and woman.

As we move beyond such myths, the use of mitochondrial acid (mtDNA) provides us with the tools to explore the true origin of modern humans. The best science at present supports the “out of Africa” model, but whether this happened once, or over multiple events is still debatable. What we do know is that mtDNA, which is inherited only from the mother, has led scientists to assume that the last female common ancestor with this genetic marker lived in Africa around 200,000 years ago, probably in the Kalahari Desert, and is the mitochondrial Eve. Obviously, mitochondrial Eve was not the only woman on earth, but she is the only woman, as far as we know, to have an unbroken lineage of daughters to the present. There’s some speculation that this was because of an evolutionary “bottleneck” about 70,000 years ago, due to climate change or other catastrophic events that drastically reduced the population.

From the time of our origin, the modern human was a coloniser and migrant; it’s in our DNA. We migrated across all the continents, populating lands whether inhabited or not, competing for resources or achieving dominance through interbreeding or violence against archaic species, such as the neanderthal. The result of this process was the modern human—the apex predator—that is recognisable today. So, migration and, of course, violence, have been part of the story of modern humans from the beginning and continue to play a dominant role in the twenty-first century.

The reasons for contemporary migration are not that different from those that drove our ancestors, with the current drivers including climate change, the colonisation or occupation of territory, or desire for personal liberty and religious freedom.

While this is big-picture stuff it does help to understand why, as a young woman, Nusra Latif Qureshi would decide to leave her home in Lahore, Pakistan, and move to Melbourne in 2001. At home she had completed her undergraduate art education at the National College of Arts (NCA) (credited with the revival of musawwari or miniature painting under the guidance of Bashir Ahmed). Her reason for moving to Melbourne was principally to enrol in a master of fine arts at the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA). Given that Pakistan’s legal system is a combination of civil law and Sharia law, where women are disenfranchised or explicitly discriminated against in marriage, divorce, and inheritance, personal freedom may have been a contributing factor.

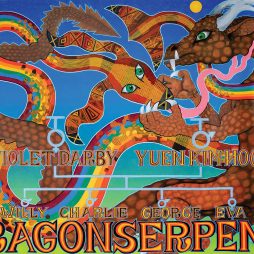

Which brings us to Qureshi’s current survey exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Birds in Far Pavilions, thoughtfully curated by Dr. Matt Cox. Cox has strategically used the three galleries and a foyer space to create a narrative of Qureshi’s thirty-year career. The first gallery focuses on her early miniature paintings, or musaviri, as Qureshi refers to them. They include five works that were made while the artist was a student at the NCA and reflect the changing politics of the place in which she was living. Her subsequent works from this early period all have a jewel-like intensity and play with colour, use various aesthetic and compositional devices, such as borders and margins, and subvert traditional storylines, where grandees are replaced with subjects that signal the concerns of women. Obviously, this is not an original idea as it has been a feminist trope for several decades, but it is effective in this context. Qureshi’s works from this period are intelligent and quietly nuanced but lack the political punch of the miniature paintings of Pakistani US-based Saira Wasim (also a NCA graduate), particularly her series of paintings that deal with honour killings.

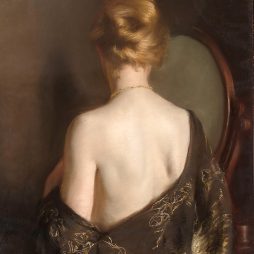

In the middle gallery a series of vitrines contain, as Qureshi explains, “hand-picked objects, paintings and photographs from the AGNSW collection and objects from my own studio.” The origin of such displays owes a debt to the English antiquarian Elias Ashmole, who donated his cabinet of curiosities, or wunderkammer, to Oxford University and became the Ashmolean Museum. Qureshi demonstrates a naivety here as it is not clear whether she understands the implications of using such objects, many of which were used, and continue to be used, to express the tastes, preferences and world view of a certain class, particularly from countries with imperial ambitions.

In the final gallery there is a decisive shift in the works as Qureshi navigates a new country, and its values and customs. She was surprised to find that Melbourne lacked the cosmopolitan vibe of Lahore. After her years as both a student and teacher at the NCA, which she found to be international in outlook, Qureshi found her experience at the VCA rather isolated and insular (it is still a problem under the current leadership). Moving away from your own country gives you a certain freedom and anonymity, and allows time for reflection.

For Qureshi, it heightened her senses, and this was manifested in the use of cultural symbols that for locals had receded and carried little meaning, such as the image of the late Queen Elizabeth on Australian currency. Perhaps, this is arguably a form of migrant anxiety. In a similar vein, on my first trip to Hawaii, I asked a local why their state flag had the British Union Jack depicted as a canton (placed in the upper-left corner); they had no idea that it was the British flag.

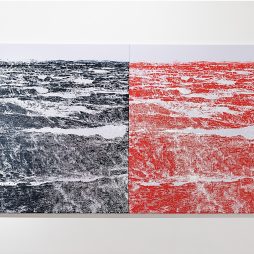

In Qureshi’s later work the influence of the painter Jon Cattapan, who was her lecturer at the VCA, is evident, particularly in her use of stencils, silhouettes and photomontage to create multilayered surfaces. Certainly, the most compelling of these works deal with the complex issue of refugees or “boat people,” as politicians of all stripes cynically call them, and specifically the Tampa crisis. After a period of initial cultural dislocation Qureshi found a subject that resonated with her in her new homeland.

Regardless of when Qureshi, or anyone else arrived in Australia, we are all colonisers and migrants. These terms, which at first glance appear to be distinct, are in fact the unresolved Gordian knot of contemporary Australia. Qureshi, is one of many artists, who is attempting to untie this knot.

Birds in Far Pavilions is an ambitious exhibition that would have been improved without the overweening exhibition design. It is, however, accompanied by a handsome catalogue, with a number of scholarly essays, particularly Sacred boundaries: leaning from Lahore by the previous gallery director Dr. Michael Brand. One hopes that the AGNSW will continue to mount exhibitions that reflect and celebrate our culture, in the broadest sense, under the new directorship of Maud Page.