Patricia Piccinini

It has taken some time for the Australian art world to get its own head around the genetically challenging and often startling creatures and concepts of Patricia Piccinini’s art. Perhaps most popularly known for her gigantic, multi-mammaried ‘Skywhale’ that floated serenely above all the controversy in Canberra in 2013, Piccinini’s work has been shown in Venice, Brazil, the US, London, Germany, Japan, China and Taiwan, and is now being prepared for an overdue, major exhibition next year here in Australia.

“The work of Patricia Piccinini is an enigma to be deciphered by each one of us. If our reaction before these bizarre creatures is, in the first moment, one of revulsion or estrangement, in the next instant the artist manages to arouse feelings of empathy by having us face the profound gaze of each one of these beings.”

These are the opening thoughts of curator Marcello Dantas under the delightful heading, “Love at Second Sight”, for Piccinini’s solo show, ComCiência which toured three venues in Brazil for eight months last year courtesy of the country’s Ministry of Culture and the Banco do Brasil. Hundreds of thousands of Brazilians engaged. But who in Australia knew?

Who knew, too, that Piccinini had 2016 solos at the Yu-Hsiu Museum of Art in Taiwan, in Essen and in a commercial gallery in San Francisco?

Marcia Tanner from Californian gallery Squarecylinder.com pointed out, “If Piccinini’s work belongs anywhere it’s in the Bay Area, San Francisco, centre of research in genetic engineering, biotechnology, bionics, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, robotics — the whole gamut of industries dedicated to blurring the distinctions among human, animal, plant, machine, electronic and digital forms of existence. The potential consequences of these technologies, and the emotional, moral and existential questions they raise, are what her work is all about.”

Patricia Piccinini was born in Sierra Leone after her English teacher mother married her Italian school-building father there. They tried living in Italy, but moved on to Canberra, where Piccinini did her schooling. The Victorian College of the Arts then called to someone who can still recall a painting like Enzo Cucchi’s.

Questions are often asked about the value of Australia’s heavily-promoted participation in the Venice Biennale. For many artists it seems to lead nowhere. But Piccinini’s 2003 appearance in Venice provoked no fewer than 114 articles and reviews around the world and has surely led to her international appreciation as a provocateur whose thoughtful work ticks so many contemporary boxes – from genetics to feminism to climate change.

She even ticked a box for the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria, which decided that doom-laden adverts had failed to achieve an improvement in that State’s death toll on the roads. The Commission turned to Piccinini to challenge the imagination with ‘Graham’, an evolved human who just might be able to survive a serious car crash. “I’m an artist who engages with ideas outside the art world,” declared Piccinini in explanation of why she took the project on – although, interestingly, ‘Graham’ was toured around the State’s regional art galleries rather than shopping centres or blackspot sites, and has an online, X-ray presence that has topped two million hits.

‘Graham’ required 10 months of research with accident experts and trauma surgeons to invent a scientifically possible car crash survivor. Writing for Artlink last year, Sophie Knezic observed, “When significant parts of our anatomy are biotechnologically improved, to what degree do we remain human? The strength of Piccinini’s cyborg bodies is that they do not disguise their biotechnological modifications. Quite the contrary; they confront us in all the potential gruesomeness of prosthetically built or genetically engineered amendments.”

It’s questions like Knezic’s, “to what degree do we remain human?” which the Mona Lisa-smiled Piccinini hopes to provoke from the quasi-industrial setting of her busy atelier in the backstreets of Collingwood. “Unlike a writer such as Peter Singer, I don’t have strident solutions to all the problems of modern life. I want to expand on the conversation with my community and hope people get back to me with their thoughts. It’s the only way we can become a community that can deal with hard ideas. And art can keep us close to such ideas until we find ways to deal with them.”

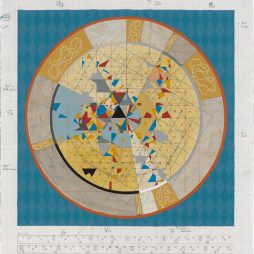

Piccinini’s art has to be empathetic to keep us that close, but it’s so inventive that people seem to need to invent words to analyse the effect. Curatorial maven Juliana Engberg picked on “virtuality” – seeming to be real – in her catalogue essay about the artist for the 1999 Melbourne Biennial: “Virtuality extends the idea of virtual reality to the point where it is active and creative.”

And what could be more active and creative than ‘The Dancer’, Piccinini’s iconic work of 2016. Seen at the Greenaway Gallery in Adelaide, the MCA’s New Romance show in Sydney and in San Francisco, this tiny chimera with a winsome monkey face grafted onto a pair of shoes that are up on stubby tip-toes and dancing, comes in a mirrored case to emphasise the blending of forms. But it’s that face that has done all an artwork can do to win its audience.

In a way, Piccinini’s creations with eyes are a cop-out – they distract from her message. The chunky, faceless, tattooed torso hanging from a nearby wall at the MCA was much harder to love, more challengingly conceptual and part of a narrative that was the essence of her installation, Alone with the Gods. Audiences had to take a mass of information on board to go along with that ride.

However the ride was an essential part of this “chemically female” artist’s work. I don’t believe a man could have created her opus – although she herself acknowledges the indispensable dramaturgic work of her partner in art and life, Peter Hennessey. Words such as love, intimacy, fecundity, mothering and birth pepper her commentary, and the narrative core of Alone with the Gods was the displacement of the pushing, technocratic male by his nurturing daughter “who is free to bring things unnaturally together to achieve what society needs, not just what we might want,” explains the artist – who is also, just possibly, that daughter.

Then there’s ‘Joined Figure’, created last year for San Francisco. “A very difficult work,” announces Piccinini, “I found it very hard to imagine being this creature” – a fascinating insight into the artist’s modus operandi. The work is two conjoined human trunks, one male, one female, “in incredible intimacy. A body that’s not an individual, their sexuality becoming so fluid, we have to accept it.” Mind you, the genders are only apparent via their hair – the female’s locks capped by a flesh-coloured motorbike helmet – such a trademark icon of Piccinini’s. She can disturb by giving her helmet a shape that doesn’t match the normal skull, raising questions about the head it’s designed to fit and the nature of the brain contained therein. Could it be the diseased head of a Darth Vader?

Is ‘Joined Figure’ a success? For that, “it has to be as beautiful as I find it,” owns Piccinini. Her closest interpreter, Hennessey adds a proviso, “What she sees is a beauty in these things, and she invites us to see that too. Whether we will or not is almost immaterial, compared to the faith that she places in us in believing that we will. I think that this is what saves the work from being either simplistic or didactic.”

Her giant ‘Skywhale’ balloon was also beautiful to the artist, but “in Canberra, she was much maligned,” reveals Hennessey. “It cost $170,000 to build in Bristol – as part of the Canberran Centenary celebrations – and people thought that was too much for art! I suppose she disrupted expectations – why would a whale fly? Well, whales evolved from hoofed animals that went back into the water and developed huge brains and bodies, and kept their hair! Why wouldn’t this wondrous nature be capable of evolving to fly? And why wouldn’t the sight of her overhead in a hot-air balloon town stimulate thoughts about evolution? She certainly developed a small support group who felt very strongly about her. Perhaps she can go back to Canberra some time and be cheered and waved to by people?”

The biggest hurdle Piccinini identifies this year is an academic one – for which this master of mind over matter has been taking speech lessons. She finished last year giving the graduation speech at the Victorian College of the Arts, her own alma mater, which responded with an honorary doctorate.

Earlier this year Piccinini become the VCA’s Professor of Enterprise, determined to encourage a future generation of artists to believe in themselves, stay in Australia and build their careers sustainably here. And she wants it to be a successful woman artist offering this motivation, and offering it confidently. “I’ve been told to leave many times – but that’s not the way to build our own culture, is it?”

EXHIBITION

Patricia Piccinini – the struggle and the dawn

(31 Aug–30 Sep)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.