Parlingarri Amintiya Ningani Awungarra: old and new at Jilmara Arts UNSW Galleries

On the second floor of Parlingarri Amintiya Ningani Awungarra was a room dedicated to “The first old ladies of Jilamara,” one of ten thematically devised spaces across the UNSW Galleries. The display hinges on four Kutuwulumi Purawarrumpatu (Kitty Kantilla) paintings on white grounds, claimed as a radical stylistic departure when they were first exhibited in the late 1990s. However, this innovation was more pragmatic: impatient to start work, Kantilla grabbed an unprimed canvas and added a “new” style to her abstract repertoire, previously all made on black surfaces.

Within a mix of translucent paintings, etchings and lithographs, “The Queen of Jilamara” (as Kantilla was affectionately known), is accompanied by Taracarijimo Freda Warlapinni’s quivering marks including an exceptional bark in gritty red and yellow ochre. Both artists passed away in 2003 and held an esteemed place in the art centre at Milikapiti; through their example, younger artists observed an inventive freedom in contrast to the precise geometric jilamara (designs, painting) being produced at the time. Two works on paper from 1996 by Maryanne Mungatopi—an honorary old lady in this mix, as she died aged thirty-seven—exemplify this formal style, though her late work was resolutely figurative.

Moving through this selective thirty-year survey, the distinctive qualities of Jilamara’s core artists become clear. The “old and the new” of the exhibition’s title reflects the creative dynamics of Jilamara Arts, reinforcing the idea of ancient and contemporary cultural expression coexisting, Tiwi parlingarri (creation time) and their artist-forebears, providing an endless stream of inspiration.

Curated by Jose Da Silva and the Jilamara artists–now a standard collaborative model for such exhibitions–creative and social companionships shine. Conrad Tipungwuti and Timothy Cook’s room is a case in point. Both have worked at Jilamara since 1997 when the supported disability service Ngawa Mantawi was integrated into the art centre, and each riffs fluently on large square canvases with a dominant circular motif. These imaginative extensions of the kulama ceremonial dancing ground operate on a scale that far outstrips the human body or the ironwood tree trunk—though the finest tutini (carved poles derived from funerary traditions) are in this room, collaborations between Cook and sculptor Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri.

In the following room, Janice Murray applies bright ochres to her face on camera, beside new bark paintings by Pedro Wonaeamirri, a master of the traditional wooden painting comb kayimwagakimi. Jilamara’s leading ambassador, over decades he has used the comb in his pwoja body paint designs. While Wonaeamirri works in all media, the intently measured bars on the undulating rhythm of stringy bark are outstanding. Raylene Kerinauia is another early adopter of this unique Tiwi tool, and Kaye Brown uses her comb to create a veil of textured ochres in blocks of colour. These exquisite pieces are also a personal and professional triumph: in 2024, a shipment of her paintings was destroyed by fire enroute to the Art Gallery of South Australia for the Adelaide Biennial.

Other recent stars include Michelle Pulatuwayu Woody Minnapinni and the late Dino Wilson, both working at large-scale, and small barks by the youngest exhibitor Arthurina Moreen—better known as a rising star in women’s AFL. Equally vital to Tiwi culture is song and yoyi (dance) performed on Melville Island and presented here on large digital screens.

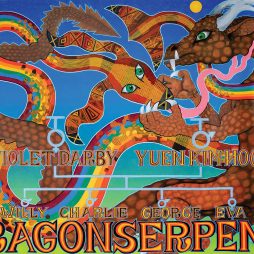

In Tiwi cosmology, the ritual drama revolves around the ancestral figures Purukaparli, his wife Wai-ai (or Bima), his brother-in-law Japarra (the moon man) and baby Jinani. This pukumani story is most literally illustrated in Walter Brooks’ collection of carvings, while Johnathon World Peace Bush’s The Last Supper and the Big Breakfast, 2023, draws connections with over a century of Catholicism at Bathurst Island. Hanging alone in a darkened room as a metonym for the pukumani and the mortal danger of misplaced seduction: ten white-on-black barks by Columbiere Tipungwuti portray Japarra, his penis as central to the story as the moon and stars.

A range of “messenger birds” also feature in this narrative. Patrick Freddy Puruntatameri’s parliament of owls occupy the ground level foyer, greeting and farewelling visitors. At the doorway, two towering owl tutini set against the campus “forest” of giant fig tree invites a sense of scale if not finesse, while Janice Murray’s owl painting is as neat as if it was machine cut.

For over 110 years, Tiwi have been engaging with outsiders interested in collecting and documenting their art, including the seventeen tutini that hold court at the Art Gallery of NSW. Since 1989 Jilamara Arts has been a vital conduit between artists and audiences, as well as facilitating artist’s engagement with twentieth century museum collections of Tiwi art. Comparisons between generational styles and aesthetic trends will always continue, and this exhibition is one more fine example of how artists carry their rich histories forward.

EXHIBITION

Parlingarri Amintiya Ningani Awungarra: Old and New at Jilamara Arts

24 May – 10 August 2025

UNSW Galleries, Sydney

.

Images courtesy of the UNSW Galleries, Sydney

This article was first published in Artist Profile, Monthly Newsletter, August 2025