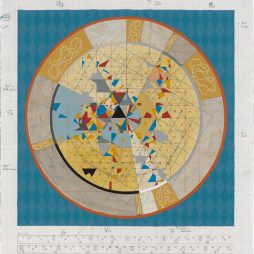

Kevin Lincoln: The Eye’s Mind

Kevin Lincoln's works speak for themselves. There was no fluff or hype about the artist when he spoke to Richard Morecroft and Alison Mckay for Artist Profile in Issue 21. And in recognition of the impact of this quietly spoken Australian artist, the Art Gallery of Ballarat is surveying the strength of Lincoln's career. Opening 23 April, it focusses on the evolution of over some twenty-five years of mature and critically acclaimed work, from around 1990 to the present.

Our first encounter with Kevin Lincoln is as a headless body. The industrial metal doorway to his warehouse studio is just hobbit-sized and as the door swings open in response to our knock, only legs and a torso are revealed. Before bending down to step inside, we notice some hand-painted words above the entrance – “Ecole de Dessin” (School of Drawing).

The space within is filled with light, collected objects and the paraphernalia of painting. But even with all the masks and plants and bones and bowls, this studio is impeccably tidy; a private world clearly occupied by an ordered mind.

Kevin, head now visible, is welcoming but politely doubtful about the wisdom of an interview. Despite the fact that he’s a critically respected artist, he is a quiet and private man – “no self-promoter” as he puts it – who prefers to focus his energies entirely towards his artistic output.

He has called Melbourne home since the 1960s, after his childhood in Tasmania. Coming from a large family that wasn’t well off, he had little formal art training and worked as a welder and boilermaker. His early artwork, mostly linocuts, reflected his industrial and political preoccupations and it wasn’t until the 1970s that he began to exhibit paintings. Over the last 35 years, he has exhibited consistently and to great acclaim. Considering the longevity of his career (he is now 71) and that his works are held in major public and private collections both in Australia and overseas, it’s surprising that he isn’t more widely known.

Critic John McDonald described Lincoln as “one of the most introverted and underrated artists in this country”. However, for those familiar with his work, Kevin Lincoln is revered for his austerely powerful still life compositions, his enigmatic self-portraits and diverse etchings.

In 2010, his paintings were exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales alongside ceramic works from the revered 19th century Japanese Buddhist nun, Otagaki Rengetsu. And though they’ve lived in very different times, their austere aesthetic and simplified lifestyles have much that resonates. One of Lincoln’s still life works featuring a Rengetsu bowl was acquired by the gallery.

His restrained and spare still life paintings – often multi-panelled – are perhaps his best known works. Uneasy spaces surround isolated objects of the everyday and favoured icons return again and again – the knife, the mask and particularly the simple white bowl. His self-portraits, though, are disconcerting and dark, taking the viewer to a contradictory zone of both exposure and concealment.

Is drawing at the heart of your work?

Yes, I think it is – hence the sign, “Ecole de Dessin”. Apparently Picasso thought that every artist should have that written above their studio entrance. I’ve always got sketchbooks wherever I go. There are boxes full of them over the years. I make my own sketchbooks and I like them to stay as books, not have individual pictures torn out. They’re not consciously “artist’s books”, they’re just work books. And I draw anything and everything.

When you’re painting, what role does drawing play?

I draw with charcoal onto the canvas first. With the large still lifes I draw a lot of things and most get painted out. I don’t make a study, like a drawing, usually – the painting happens on the canvas.

So a lot of the subject matter disappears?

Yes, especially in the big still life things. You know, I’ve got a vase and then twigs and some knives and fruit… I start wondering what should go where and when I start painting, it reduces down to just a few things on the canvas. The painting dictates the terms but without me knowing why it looks right, or even caring.

And the defining quality of those still life works seems to be the sense of space around the objects.

Yes. That’s usually done with the wide flat brushes. Otherwise I just use regular artist’s brushes. But I don’t have a sort of method – I’m not a tonal realist, for example. The Meldrumites are locked into this almost scientific method. I don’t do that. I can be freer, I can do what I jolly well like. I don’t know much about tones and stuff. I often say to people, I don’t know anything about colour. I don’t know colour theory. If I want to bring green in I just use a tube – it doesn’t have to be a cool green or a warm green. I don’t think in those ways. I just do what the picture needs. I don’t rationalise what I’m doing; I just work at it till it looks right and that’s it.

Tell us about your use of multiple panels.

Well, it’s an entirely different proposition painting a three- or four panel work than painting a single canvas of a similar size. Those divisions, for some reason or other, they’re important. They’re something to hit against.

And an object wouldn’t be the same if it wasn’t crossing over one of those joins between the canvases…

That’s right. If I put a knife in, it’s got to take into consideration not just the overall composition, but where it sits on that particular panel in relation to the other one. It’s quite a different proposition. I think I like the triptych panels more because I like oriental paintings and screens.

In some of your still life paintings there seems an oriental sensitivity to contemplating the forms.

Well, I have a non-encyclopaedic interest in oriental things. Hence the tea bowls and cloths. When I was married, we collected contemporary Australian ceramics. More recently, I started buying antique Japanese tea bowls. I have a couple of big black pots by a local ceramicist and I started painting them. The individual tea bowl paintings are often done from them sitting there, but it’s not always ‘look and put’. With a lot of the still life works, if I want a bowl, I know what a bowl looks like, so I just paint a bowl.

Do you have an awareness of how you decide what still life items to use?

Often I wander around for a few days going “What will I paint next?” I try various things and usually just come back to a bowl and a couple of knives; the things that are around me. I don’t go out looking for something that might fit into a painting. It’s just what’s about.

But I think you don’t need to know so much about me – more about the work. Flaubert said, “It’s the artist’s job to make the world think that he didn’t exist”.

Which brings us to the self-portraits and their lack of obvious features – particularly the eyes. Are they in a sense indicating that there isn’t much about yourself that you want to share?

The self-portraits… I don’t know what they’re about. It just sort of happens intuitively – I don’t think “I mustn’t paint the eyes because I don’t want them to look too closely”. It’s just the way the painting needs to be; it’s the way it happens. The painting dictates the terms of its creation.

There’s a self-portrait with a fluorescent tube behind you – you’re just a silhouette. No details. It may have been painted at night…

I paint whenever I need to – at three o’clock in the morning, it doesn’t make any difference to me. I can continue the same painting by day and night.

In fact, one of your studios had no external windows at all… yet when you walk into this studio, the first impression is of light. How did that affect your work?

I wondered, after I found this space, “What’s going to happen to the work?” And… nothing. Absolutely no difference at all. The work is just as dreary and dark as it ever was!

Because I could work in that windowless space, I never depended on ideal light – lots of artists go on about south light. So maybe those years set my head… and it doesn’t make any difference now.

Much of the time you’ve been focused on self-portraiture, but what inspired your series of etched portraits of other painters and people involved in the art world?

Well, I’m not sure. I think Rick [Amor] and I had a session one day – it was a long time ago, in the 90s – and we made etchings of each other and I think it grew out of that. I tried someone else and it all snowballed. I paint and draw and etch self-portraits, but I only ever etch other artists – I don’t paint them. But I’ve always got a couple of plates ready for any artists wandering past! Quite a lot of my etchings are engraved onto perspex, so I can be very free.

One of the other intriguing things was your interest in the idea of “using the difficulty”.

Yes, I don’t take an easel out when I’m drawing and usually don’t take a stool, so I’m sitting on the ground. It’s uncomfortable and the wind’s blowing the paper around. I don’t mind that, you know, coping with that difficulty but also using the difficulty, so I don’t get too finicky; too comfortable.

Many artists love the companionship of going out into the landscape together, but it sounds like you’re the opposite.

Yes, that’s right. People wanted me to join a group going up to the Centre but I can’t think of anything worse. They’d all have ‘show and tell’ and sit around the campfire singing ‘The Lumberjack Song’. That’s not me. I’m very protective of my solitude and I live here quite happily on my own. I don’t do lonely – I can be here for four days without going out of the door; just working and reading.

I have artist friends, of course, and we see what each other is doing; but there’s no room in that for criticising work and I wouldn’t welcome that. A lot of artists go back to university to get a Master’s and they say they want contact with other artists – I say that’s the last thing you need. You’re an artist when you’re standing in front of your easel.

Looking ahead, is the landscape an area you’ll continue to explore in exhibition terms?

Well, [my Melbourne gallery] Niagara is very interested in showing the landscapes next year. But the future doesn’t concern me very much these days – it gets smaller and smaller from here.

Exhibition

Kevin Lincoln: The Eye’s Mind

23 April – 19 June

Art Gallery of Ballarat

Courtesy the artist, Art Gallery of Ballarat, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, and Liverpool Street Gallery, Sydney.