FILM REVIEW | Ghosts in a Cave: William Kentridge’s Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot

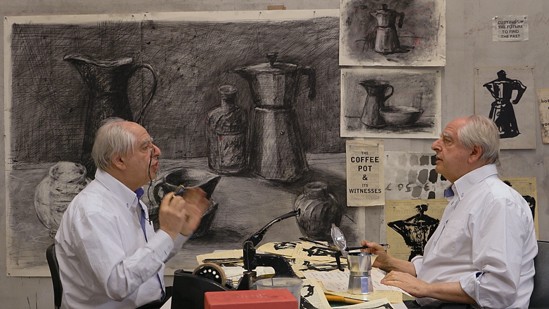

The title 'Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot,' a series of nine short films by William Kentridge, promises an absurd(ist) and idiosyncratic self-examination. Each episode fulfills this promise, and the self-examination has a literal quality, with Kentridge duplicated thanks to green screen technology.

William Kentridge’s Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot opens with the artist pacing back and forth against the backdrop of his studio, with remnants of a sketch barely legible on the wall. The film cuts and the same image is projected on an open sketch book, with Kentridge rendered a phantom on the page. Two hands, Kentridge’s hands, start arranging paper cut-outs-cum-sculptural forms on the paper, before drawing a red scribble, which becomes a path for the still pacing, projected Kentridge.

The sequence recalls various cinematic instances of an animator and a cartoon interacting, including from the silent era. Such trickery tends to afford the illusion of instantaneous reaction. This is only partially so with Kentridge’s opening, as Kentridge’s translucent form is evidently projected. As with memory, it can nevertheless be modified and revised. Further, we witness two Kentridges in conversation, both contradicting what the other is saying, even quibbling about the time of day. At this point it is clear that this will not be a conventional documentary, if a documentary at all, given the sparse glimmers of biography across nine episodes.

This is not the first time in which Kentridge interacts with a doppelgänger, with Kentridge deploying signature devices and familiar terrain. Still, through these discussions with himself, we learn of Kentridge’s habit of circling the studio, affording “a peripheral thinking, allowing ideas to emerge that are at the edges of one’s thinking.” The first episode is dedicated to explaining this associational mode of creativity, where “you start thinking you’ll do a picture of the whole universe, but you end up with a coffee-pot.”

But Kentridge is idiosyncratic, not solipsistic. Indeed, there’s something near-universal about his self-conversing as the films were made during COVID and Kentridge monologues? / converses? about the spatial separation to his family. And the series is also about collaboration as Kentridge is shown working with Black artists, dancers, and singers, whose own skills are justly celebrated.

William Kentridge, ‘Self Portrait as a Coffee-Pot: Vanishing Point (still) Episode 3, 2022-2024.

Although Kentridge is best known for his use of charcoal animation whereby the drawing is smudged amid erasures, Kentridge practices not only include sculpture but also theatre and opera. A white South African, he is unafraid to tell his collaborators about their colonial history. This may come as a surprise for viewers accustomed to the “woke” art world. In a conversation at the Museum of Fine Art, Boston, the postcolonial theorist, Homi Bhabha, mentioned finding Kentridge’s lack of fear in this regard “refreshing.” But then Kentridge has pedigree: his father, Sir Sydney Kentridge (1922-), defended Nelson Mandela, and his mother, Felicia Kentridge (1930–2015) was also a lawyer working against the apartheid system, and co-founded the Legal Resource Centre, representing Black South Africans. Kentridge himself was an anti-apartheid activist and campaigner.

While I feel that some of Kentridge’s recent works lack the biting quality of his early animations that had greater proximity to apartheid—this series is an example of a more quirky but gentle approach—political layers are omnipresent. These layers are incarnated through his aesthetic of collage and palimpsest and the way he blends a fixation on twentieth century art movements, such as Dada and constructivism, with political struggles. In Episode 8, Kentridge explores the Russian revolution and even acts out Bukharin’s chilling show trial, which has an absurdist intonation. When Bukharin stated that “I am speaking sincerely,” amid mocking laughter in the room, Molotov replied, “And we are criticising you sincerely.” When Bukharin said, “it is very hard for me to die,” Stalin replied, “And it’s easy for us to go on living?” Kentridge appears split when conversing about the aim of making art about the Russian revolution and dealing with such perverse tragedy. A radical Kentridge argues to a more sceptical and conservative Kentridge that ” Without utopia there’s a gap, a lack, an emptiness. I mean, what’s left? Hedge funds, TikTok, and golf?”

Kentridge’s series is not didactic. In the final episode, Kentridge instead cites Plato’s allegory of the cave. The cave, for Kentridge, signifies shadow and ambiguity, but also reflection and doubt. Kentridge in a doppelgänger-induced cross-examination, spells out “how sometimes the light is too much to see by and one needs, a shadow, one needs a darkness to stay in the cave, an illuminating shadow.” Fittingly the argument is visualised when glare from a window effaces a charcoal image, with the over-exposure ending only when Kentridge lends his shadow. The shadow, contra traditional understandings of Plato, no longer conceals but uncovers.

While the series lacks a narrative arc—thus, not exactly bingeable—this is the point: issues, historical moments, and ideas encircle, much as Kentridge circles his studio, appearing, smearing and disappearing. But then, life is fleeting, absurdly so, and this can be registered as both joyous and tragic as only the smudgy repetitions linger in the quest to leave a mark.

Dr Aleks Wansbrough is a writer, lecturer and artist, interested in film, art, and philosophy.

This article was first published in Artist Profile Issue 71.