REVIEW | Pulse: Christopher Hodges

In the 1970s, when Christopher Hodges was an art student at Sydney’s Alexander Mackie College of Advanced Education, the late modern concept of an international style of abstraction retained currency for many Australian artists, even as the notion of internationalism was being criticised as a reinforcement of the cultural power of the United States and Europe. Today, Hodges’s paintings and sculptures evince a formalism with roots in the late modernist phase, but the intervening fifty years have seen a localisation of his approach which is telling not only about the life he has lived but the changes that have occurred in Australian art in that time.

Pulse, the title of his current exhibition at Utopia Art Sydney, alludes to the rhythmic equilibrium of parts that has long characterised his work. As a painter Hodges strives for simplicity and order, alternating between geometric and natural motifs; as a sculptor he realises a similar range of forms in solid materials that stand their ground in environments beyond the gallery. His work lives through its facture: striving for elegant efficiency, he makes no direct declarations of meaning, trusting that materials become articulate when nourished by the maker’s experience.

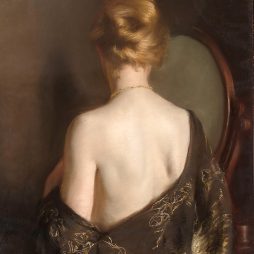

The qualities of the large paintings at Utopia vary from the pink and brown, checkerboard clarity of Scan, 2025 to the busily chattering Code, 2025, redolent of a manuscript or some obscure, communicative imprint. In smaller paintings on paper the brush is allowed to escape its geometric boundaries and glide freely, the colours acquiring a deeper mottling. In Hodges’s 2023 exhibition Country, similar elements were deployed in paintings with strong divisions between skies and mountain-forms, but the new paintings are resolutely non-representational, recalling a lineage that includes Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin among others.

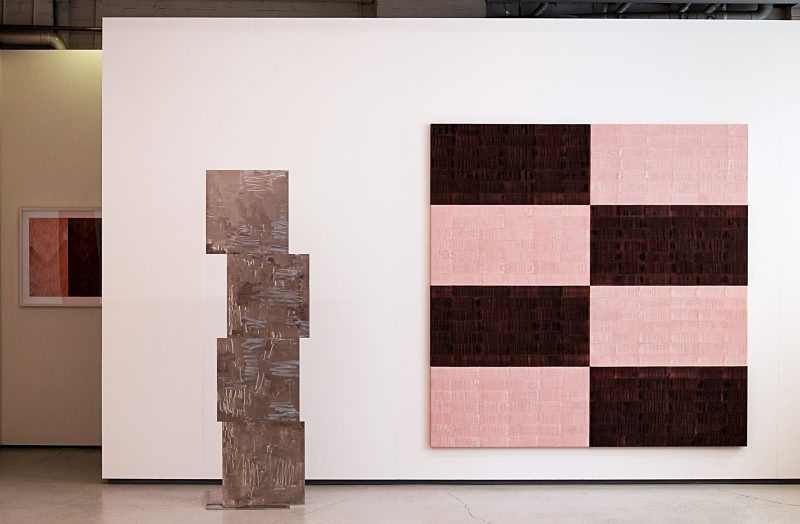

Installation view, Christopher Hodges, Pulse, 2025, in view left, Le Grand Nu Deux, 2015, and Scan, 2025, Utopia Art Sydney, Gadigal Waterloo

The richness of colour in Hodges’s paintings becomes apparent in time, aided by the changing daylight. What first appears as a straightforward black turns out to be a variegated surface of purple over orange et cetera, through multiple layers; a nearly monochromatic pink is actually titanium white over orange, the varied pressure of the hand doing enough to eke a wide canvas into a sustained illusion of depth. It is easy to underestimate the skills of painterly realisation here: Hodges varies the weight of touch (but not too dramatically) at regular intervals (but not too regular), all the while ensuring that intentionality is held in the middle ground, for these paintings would fail the moment the artist became too conscious of their hand’s movement or, conversely, insensitive to the tool. In Pulse the atmosphere of absolutism that attended late modernism falls away as we witness a person of our time, working to enliven a flat plane with simple materials and the very old question of how to coax a surface to life.

Christopher Hodges, Japan Black, synthetic polymer, paper, 56 x 56 cm, and Japan Red, synthetic polymer, paper, 56 x 56 cm, Utopia Art Sydney, Gadigal Waterloo

Accompanying the paintings are two freestanding sculptures consisting of sheer pieces of stainless steel, roughened with a grinding tool and arrayed down a vertical axis. Le Grand Nu Deux, 2015, refers to Braque’s 1908 painting of a robust, standing woman while its spindlier sibling Mirage, 2023 extends a shattered zip from floor to ceiling. The relatedness of compositional thinking between the paintings and sculptures is clear: they are all about stacked quadrilaterals and shimmying touches, but the slow-dawning play of reality and illusion that is intrinsic to the paintings does not eventuate through the sculptures. Can such shiny exteriority hold mystery, and if delicately sensate mystery is not the point here, what is?

Christopher Hodges, Stormy Weather, synthetic polymer, paper, 56 x 56 cm, Utopia Art Sydney, Gadigal Waterloo

Hodges’s art gives few clues as to his autobiography and he would likely prefer that the work spoke for itself, but his artistic enterprise is cast in a different light when the wider story of his professional activity is acknowledged. As founder and Director of Utopia Art Sydney he has been an artists’ agent for thirty-seven years. Perhaps more than any other local artist / gallerist, his work holds direct echoes of those he works for. This is not a case of pastiche, rather that the artists he represents closely reflect his aesthetic convictions. There are in Hodges’s work parallels with Helen Eager’s repeating, hard-edged shapes, Angus Nivison’s pairing of red and black, Richard Larter’s rolling bands of acrylic colour, Peter Maloney’s seismographic zigzags, Kylie Stillman’s low-relief symmetry and so on.

Installation view, Christopher Hodges, Pulse, 2025, in view left, Stormy Weather, 2024, Mirage, 2023, Japan Black, 2025, Japan Red, 2025 and Screen, 2025, Utopia Art Sydney, Gadigal Waterloo

It is not so easy to draw equivalence with the work of the great Aboriginal painters he has worked for, such as Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Gloria Petyarre and Makinti Napanangka, for the dimensions of time and story in their paintings are of another origin. But the sense of deep inhalation and exhalation in their painting is something Hodges likely aspires to, and the complex locality he has been endowed with as he shuttles between the studios of the eastern seaboard and the artistic communities of the continent’s interior has surely propelled his work beyond what could have been a generic, international style to a much more distinct and distinguished state. If this is formalism, it is of the twenty-first century Australian variety.

Exhibition

Pulse

1 – 22 November 2025

Utopia Art Sydney, Gadigal Waterloo

Images courtesy of the artist, Allana Mcafee, and Utopia Art Sydney, Gadigal Waterloo

Joe Frost is an artist and writer based on Gadigal Sydney