PROFILE: Anna Johnson in the Studio

Anna Johnson came late to painting. She’s been a writer for most of her working life, putting visual art onto the page through criticism, commentary and story. While she’s always drawn and made watercolours, writing was where her primary creative focus lay. Six years ago, she took a studio and began to paint large abstract canvasses. The results are extraordinary, writes Susie Burge.

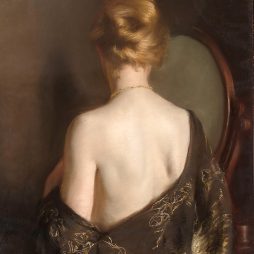

Walking into Anna Johnson’s studio is like passing through a portal into another world: a flight of rickety wooden stairs leads to the top floor of a turn-of-last-century building where Johnson serves tea in ornate vintage china cups, a lapdog appears to have emerged straight from a late Rembrandt oil painting and the artist herself rarely stops talking about art. Johnson has been a storyteller for most of her adult life, translating visual art onto the page through narrative, criticism and commentary. She’s written on a diverse range of artists, from Australians Ann Thomson and Simryn Gill to the American painter Sean Scully. She has a way with words. And now it appears Johnson has a way with paint too. Around us, in vivid contrast to the dilapidated charm of the building, hang large abstract canvasses, all painted within the last few years. These astonishing paintings are sophisticated in their referential quality, yet at the same time the work feels fresh and raw and genuinely original, and the colours are extraordinary.

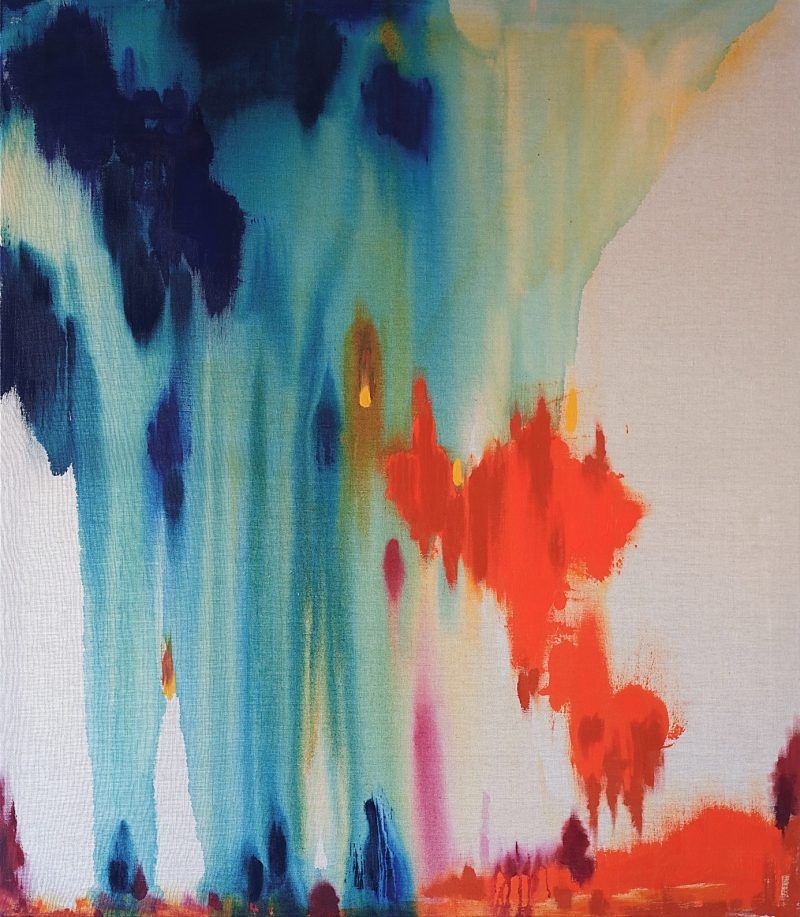

Johnson paints with her hands, as well as with brushes. She uses acrylic, oil stick, oils, house paint. Painting is visceral, a bodily experience. So much so, that she terms some of her works blood paintings. “I have a real nostalgia for bleeding. There are no rituals for letting go of beauty and the tree sap of fertility, so sure, a canvas can be an erotic souvenir,” she says. But she resists closure, even in her own interpretation of her own creation. These paintings could be as much about atrocities in war-torn countries, she suggests, as much about collective distress as about personal experience. There is intense emotion, there is release, there is catharsis, there is celebration, there is grief, and love and the anguish of loss perhaps, and her work is in no way saccharine, but even though paint may literally look like blood on the canvas, such a literal, visceral quality is counterbalanced by ethereal beauty. In Blood Cloud, 2024 diaphanous veils of delicate pink are reminiscent of Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stained colours.

‘Bowery and Spring’, 2024, acrylic on linen, 137 x 182 cm

Johnson paints on linen and often leaves sections raw, a technical decision that foregrounds the materiality of the support itself. Belgian linen, with its neutral tone, distinctive texture and appealing tactile quality, becomes significant in the picture field, arguably equally as important as the varying shapes, colours and degrees of saturation or dilution in the application of paint and oil stick. This calls to mind the paintings of Clyfford Still, and yet also seems to reference textile art, insisting on pattern and texture. In Oh Watteau, 2024 large swathes of raw linen become voids around which vivid pigment falls and shifts. In Bowery and Spring, 2024 narrow areas of raw linen appear as smudges around the edges of jagged shapes.

The towering American art movements of abstract expressionism and colour field painting seem embedded in Anna Johnson’s psyche. She’s the daughter of senior Australian abstract painter Michael Johnson, a renowned colourist, and she spent her formative years in New York. The Johnsons moved to Manhattan in the nineteen seventies. They lived on 21st Street, just down the road from the Chelsea Hotel, hub for creatives of all kinds – artists like Jasper Johns, musicians Patti Smith and Sid Vicious. Her father’s studio was in The Bowery, previously known as skid row, with cheap rents and big spaces that made it a magnet for some of the most important artists in post-war art history, including Cy Twombly, Mark Rothko, James Rosenquist, Franz Kline and many more. Anna’s mother ran a vintage clothing store. As young children, Anna and her brother Matthew spent their days in the shop, drawing and watching black and white movies. Her mother also collected textiles from all over the globe – Balinese batiks, Suzani from Uzbekistan, Turkish kilims – and to this day Anna loves elaborate patterns, texture, exotic textiles, vintage fabric and fashion. “For me, because of my mum’s aesthetic, colour and touch are the same thing,” says Johnson. After hours, the children were dragged along to pubs and gigs and galleries. It was a bohemian childhood, and a profoundly formative one.

‘Oh Watteau’, 2024, acrylic on linen, 137 x 153 cm

Johnson has always made drawings and luminous small abstract and symbolist watercolours that she carefully keeps in a Japanese chest, but she came late to painting. “I think the most gendered thing about painting is time and space. Women with children sometimes wait half a century to get off the kitchen table and onto the wall,” she says. “With that comes a lot of momentum, ecstasy and rage.” She speaks of the first time she took a large studio to paint in. “I pretended I was Anselm Kiefer circumnavigating a large space on a bike,” she laughs. “The paintings I made were garbage but it was really liberating!”

Johnson was propelled out of language-based creative work and into art-making by seismic life events. In 2019 her parents took her to see the late waterlily paintings of Claude Monet in the Musee Marmottan in Paris. It was a creative turning point, an epiphany. “The scale and the abstraction literally blew my mind, it was kind of an aesthetic revolution to me.” Then, in 2020, the terrible isolation of Covid coincided with a deep personal loss.

“I paint to let colour replace words,” she says simply. “Decades of binary thinking. It’s a way to re-enter your body and use your hands. I think it is sad that only very small children feel free. Painting is like kicking open the door and dissolving, but it is also a transference and a deliberate plea to leave a mark. When I am gone I would be very happy for people to see the marks of rage and release left by my fingers.”

One of Johnson’s heroes is the Australian painter Tony Tuckson, his energy, feel for paint and sense of connection with the body. Daniel Thomas put it eloquently in 2002. “Tuckson’s White poles brings us back to something more important: nerves, flesh and blood and bones, the human body and its ways of making contact.”

If writing about art was “the world’s longest studio apprenticeship” for Johnson, then her father’s studio was an apprenticeship too. “Here’s half a tube of cadmium. Start!” she laughs. She revers him as a colourist. “He used to say there’s no such thing as bad colour, only a bad context,” she says. “He squeezes it straight from the tube and just lets it rock! There can be up to fifty colours battling it out in one painting.” Other influential relationships with local artists include her brother Matthew Johnson, her close friendship with mentor Elizabeth Cummings, and her admiration for the confessional bravery of Jenny Watson.

In October last year, Johnson showed new work at artist-run SLOT Projects in Sydney. In 2025, she has two important upcoming exhibitions: her first solo show at Sydney’s Defiance Gallery in March, and an exhibition at New England Regional Art Museum in October. Rachel Parsons, director of NERAM, has invited Anna to take up a residency some months prior to the exhibition, in order to engage with the space, the landscape and the community. NERAM also has some good Michael Johnsons in the collection, which adds an extra layer of reference. Parsons first saw Anna Johnson’s paintings at AK Bellinger Gallery in Inverell in 2022. “I was just blown away by the show,” she says. “Anna’s work seemed to sit in its own sphere in a way that was really exciting to me. She understands what she’s doing not only technically but also experientially. She seems to invite you to come into the painting and have that sublime experience.”

Johnson believes in “the spiritualisation of the abstract space,” a sense that can be felt across history, genders and genres, from Japanese Heian art to Monet, Frankenthaler, Rothko and Still. “Still took his paintings very seriously,” wrote critic Gary Brewer in 2024 after a visit to the Clyfford Still Museum in Colorado. “They were instruments to him to transcend the constraints of the world to find a kind of freedom.” Over the course of her life Johnson has moved between Sydney and New York, migrating back there in her twenties for fourteen years, before returning to home again. Here, in a rare unrenovated building in Sydney’s Woollahra, as the clear natural light filters in through old windows, it seems that she has somehow landed. In the alchemical process of painting, Johnson has transmuted her rich knowledge of twentieth century abstract art and her fascination with nineteenth and twentieth century textiles and made it new. These are paintings that grab you by the throat and insist to be looked at. The colours are mesmerizing – bold and saturated – there’s renegade energy and floating transcendent beauty and risk. They sing.

Images courtesy of the artist, Defiance Gallery and photographer, Anna Kucera.

Susie Burge is a Sydney-based writer.

This article was first published in Artist Profile Issue 70

Nymphaea Nymphaea, 2025, New England Regional Art Museum – All works presented in Nymphaea Nymphaea were made exclusively for NERAM as a site specific creative project

Blood Cloud, 2024-25, oil and acrylic paint, canvas, 138 × 460 cm

ARTIST’S STATEMENT: The conception of abstract painting is as wide as it is narrow. If for example a vast expanse of colour and form in a painting features a single recognisably figurative element such as a cloud or flower, it is stripped of its non-objective status and becomes the “real.” For this reason, many experimental painters of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century have been lodged within the confines of landscape. Penned into a genre that in fact many were busy subverting. Monet’s image as a decorative, a-political and lyrical artist is something I like to interrogate in my ongoing project Nymphaea Nymphaea. The waterlily murals were made in a time of industrial upheaval and heavily mechanised warfare. They were also completed on the cusp of Cubism and radical shifts toward abstract form. Physically they were composed to engulf. Chromatically they generated an immersion in surface that melted the seal between museum wall and sensual experience, revolutionary precursors to the Colour Field minimalists that were to follow.

The contradiction between pastoral beauty and global tensions is a subliminal fault line in my own work. What is the place of refined aesthetics in a time of conflict? Are painters here to reassure or reveal? The opposing walls in this show are divided into deliberately elemental palettes: Water/Fire. War/Peace.

A key fact perhaps forgotten about the Nymphaea murals, is that they were donated to France as a celebration of peace after the Armistice. The contemplative role of the museum as public space was powerfully transmuted by Monet’s pacifist ideals and the healing power of colour. Contemporary artists do no longer form “schools” as they did last century. Everything now exists as a multivalent hybrid: fractured, sometimes performative, divorced from its time. When I painted Blood Cloud there was nothing metaphoric about my palette. This work is about blood. When I worked through my quartet of Nymphaea paintings, the colours were aquatic and nocturnal. The depths in these canvases form hiding places, coves and shelter. They are objects of secrecy in a world stripped bare of private thought. The central form in Interdit is inspired by public censorship. Graffiti corrected and concealed in the night with rapid thick brushstrokes is a wellspring of forms and lines.

I generated all of these paintings to invite a walking gaze. To move from work to work as through space, entering shadow, confronting the void. If artistic influence is an ecology, then these are my seed bank. Sapling ideas about war and peace germinated by the deep-rooted wisdom of mature trees.

Anna Johnson

Erato, 2025, acrylic paint, linen, 153 × 137 cm

Interdit, 2025, acrylic paint, linen, 185 × 200 cm

Images courtesy of the artist and New England Regional Art Museum, Armidale.

EXHIBITIONS

Nymphaea Nymphaea

3 October – 9 November 2025

New England Regional Art Museum, Armidale

Nuage et Vide

26 March – 2 May, 2026

Kutlesa Gallery, New York