Belem Lett

This is a line that never ends

Yes, it goes on and on, my friends

Some people started seeing it, not knowing what it was

And they’ll continue seeing it forever just because.

Desire lines are the ultimate unbiased interpretation of natural human and animal intent – referring to tracks worn across grassy patches that generally represent the most easily navigated route between origin and destination. In that Deleuzian way, the theory of desire as a productive force, a force that is real without ceasing to be ideal, desire lines – collective paths – can emancipate space from the unimaginative to the fantastical, because desire has neither object, nor fixed subject. It is labour at its essence, actualisable only through practice. Belem Lett’s Gadigal-based studio, cuddling the industrial edge of Sydenham, was impossible to park near. I was following the grid like a hungry Pac-Man until finally I landed kilometres away with maps incessantly reiterating, “Proceed to the route. Proceed to the route.” Approaching Lett on foot, I saw a single car space out front of his building and sighed, if only I’d followed my nose. Something Lett does so comfortably in his painting. I was jealous. But, no time for that, proceed to the route.

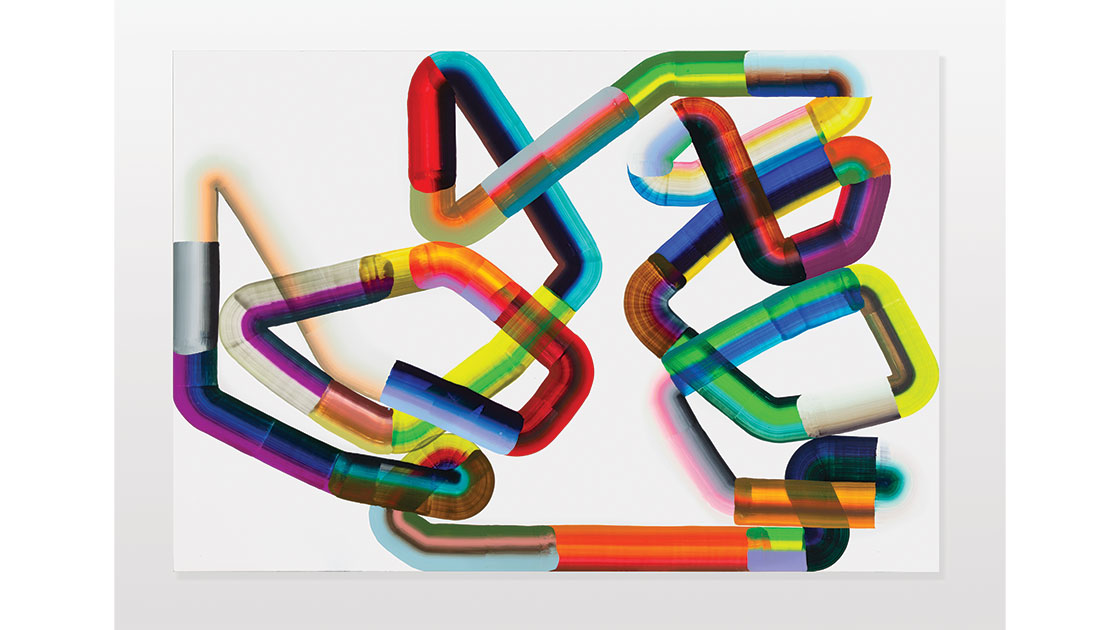

“Meadow” is the word Lett exhales when I ask him about his new paintings to be shown at James Makin Gallery. “Meadow!” I replied. Yes, I see this; expansive fields fearlessly fertile, light so lit it can’t be any brighter, grass, green, colour – the word “meadow” is the password to Lett’s paintings. Aluminium composite panels prepped with gesso and marble dust, or just raw-brushed aluminium, feel referential of Lett’s burghal surrounds – yet the licks of oil paint feel more vegetal, more sideways than gridlocked, like a set of painted pathways through the artist’s mental or psychic reality. Through his nature, he paints. And because of his nature, he paints. It’s painting as a stuff that Lett feels in harmony with; referencing the history of painting through the action of painting while painting a painting. Lett cares about acknowledging what painting is – and who he is amongst it all: “What do I care about and how do I understand painting?”

The paintings in Lett’s latest show, Meadow, strike with a gallant sensitivity; capricious line-blocks of colour swerving negative space with a covetable cool, sometimes melding together, and other times ricocheting from a bend reminiscent of drunk rides home. The ultimate rule-breaker, Lett is pitting colours against each other like a punk; deranged, silly, but somehow allied by the same cause. Hello taupe, hello verdigris. There is humour, brevity, but mainly, flirtation. Like bees in the first weeks of spring – each colour and line are in constant dalliance. Will taupe and verdigris ever touch? It’s the desire of wanting them to, but the desire for them to stay put too.

Readied but not hurried, there is a lot of groundwork laid before Lett applies these lucid highways. He tells me how he likes to be prepared, conscious, so that when it comes time to flourish, his line feels easy to intuit. Whether the panels are prepared with gesso and marble dust or just left brushed, raw, it’s important to note that each line is entirely painted off the cuff – no colours decided, no bends premeditated. Lett’s trusty brush is the only thing determined (one that he points to lovingly, hanging like a guardian on the wall). He is the painter, this is his tool. In keeping with Lett’s desire to participate in history while not pandering to it, this introduction to the brush feels important. He wants us to see his hand, his movements, the fallibility of gestures – Lett’s presence is plain for all to see.

Like desire lines, Lett paints the path of least resistance by giving in to his intuition. There are the occasional colour traffic jams, or bandit bristles, but it’s in the acceptance of this ephemera that feels simpatico: “This is an expansive setting for things to take place. I like the anomalies.” Akin to Deleuze (and his collaborator Guattari), Lett is producing a desire from itself; each line functions as a circuit breaker in a larger circuit, fed entirely from its own source yet freed by another. For someone who dwells in one of the most turbo areas of Sydney, maybe it’s Lett’s grassier upbringing on the Mid-North Coast that unconsciously frees his ambitions as a painter. He’s following his own will, completely dedicated to the form of his line, his colours, his rules, his anarchy.

Out of curiosity I typed “meadow” into maps, hoping it would navigate me toward a nonexistent pasture en route to home. But no, just another passive-aggressive reminder to “proceed to the route” slithered out. I wanted to live on a line like Lett’s – one that never ends, that is rearranged and vital and adventitious. A line that hoons your citified mind into a more limber pasture where the directions aren’t meditated by efficiency, but by your desire to move. Proceed to the route? Get bent.